The Passover of Jesus

This English version differs at its beginning and end slightly from the original German one, but is in its biggest part an exact translation. (The notes are appearing at the end of the article; the article was written in 1985).

1. The fight between Israelites and Jews

2. He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish

3. Excurse about the term Baal

4. The belligerant character of Jesus’ movements

1. The fight between Israelites and Jews

The bible tells us (II. Chronicle 30, especially verse 18) that in the time of King Hiskia (= Ezechias) of Judah (about 700 BCE) the Israelites, that is to say the inhabitants of North Palestine, were used to celebrating Passover with a quite different ceremony than the Judeans, the inhabitants of the southern state, Judah, were accustomed to. The reason the king of Judea, Hiskia, invited the northern Israelites was in all likelihood because of his attempts to bring together a coalition of states against the imminent invasions of the Assyrians. This would explain why he received his northern Guests, the Israelites, to celebrate Passover with him in Judaic Jerusalem – according to the very different usages they were accustomed, but not the Israelites.

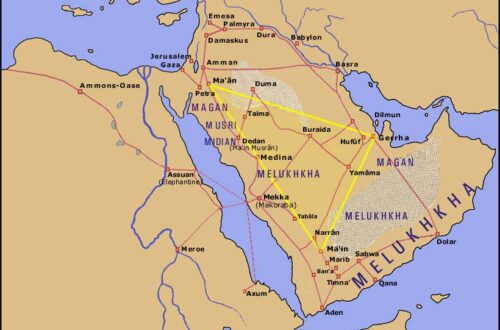

The following précis is meant to illuminate these old differences between Israel and Judah, that is to say, between the North and the South of Palestine, as they still made themselves tangible much later during the lifetime of Jesus. In post-exilic days, the Jewish priesthood did not extend any great distance beyond Jerusalem, since the priesthood with its principal, the High Priest, was not supported any longer by a nationalistic Israelite kingdom, but rather by the momentarily ruling administrators appointed by their respective alien occupation forces to oversee events (initially Persian, then Greek and ultimately Roman). Consequently the Jerusalem priesthood could exercise only very limited religious prerogatives over the ‘Israelites’ – to distinguish them emphatically – right from the outset – from the ‘Jews’ to their south. Being ‘Semitic’ is not synonymous with being ‘Jewish.’ The Israelites were indeed ‘Semitic,’ but then the Arabs to their east were also ‘Semitic’!

One may thus assume that in Northern Israel (Samaria and Galilee), the population’s cult of the adoration of their ancient Israelite forefathers and heroes at sacred grave temples erected ‘in the heights’ continued to flourish, undisturbed by the failure of the attempted cult centralization of 622 BCE which already in 586 BCE, in consequence of the total destruction of the temple, had ceased. This was likewise the case with the later modified restoration cult centered about the Second Temple from 453 BCE onwards. Indeed even up to the time of Jesus the idea of the suffering and dieing Messiah was, after all, part and parcel of the ancient popular Israelite reverence for ceremonies conducted ‘in the heights,’ the location of their holy graves. And this popular, but thoroughly pagan, idea – subject to time and place – acquires new life in the Jesus movement of Galilee (= North Israel), propelling an ancient heritage from the dormant depths to a revitalized presence on the surface again.

The antithesis between the Israelites of the Northern state of Israel (Capital, Sichem/Samaria, together with the ten tribes) and the southern state of Judah (Capital, Jerusalem and the tribes of Judah and Benjamin), stretching out over a period of a thousand years, can hardly be emphasized strongly enough nor its importance be over emphasized. Precisely for this reason in some circles, including some scholarly theological circles, it is customary today to firmly reject any reference to the Galilean Jesus as a ‘Jew,’ 1) since the gospels indicate very clearly the hostility between Jesus together with his disciples, on the one hand, and those identified as Jews. In John 1:47, Jesus appraises the person of Nathaniel from Galilee when he sees him coming, “Behold an Israelite indeed in whom is no guile.” [All citation hereafter – with one exception – from the Authorized King James Version].

A corresponding remark from Jesus’ lips containing the word ‘Jew,’ significantly, does not exist anywhere in the New Testament. In this conjunction, it is also important to note that Jesus not only comes from north Galilee (according to John 8: 48) but that the Jews consider him a Samaritan and scolded him for that reason as the devil’s messenger 2) Further, if he appeared in the south to the end of pursuing his mission in Jerusalem, then he also proposes to return to Galilee once he has fulfilled his mission, for he declares to his disciples, “But after I am raised, I shall go ahead of you into Galilee.” Let it be emphasized, then, that Jesus comes from a North Israel that has lived in antagonism with Jerusalem for a thousand years, that is to say, from a North Israel once established by ten tribes and their ‘pagan’ Messianic cultic folk religion of ‘the heights’ which centered, since far back into the past, on a cult oriented about graves and the resurrection of a ‘godly ancestor’ (anointed king) understood as their primordial tribal prince who had always been opposed by Jerusalem. 3)

He and the disciples intended to journey back to northern Israelite Galilee, emphatically conscious of the fact they were leaving Judah behind them once their revolutionary mission in Jerusalem was completed. The centralization of the cult (in 622 BCE) by the Jerusalem priesthood exclusively to their courtyard of the temple, enfeebled by the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE, was gradually, but systematically being reaffirmed (among other things by integrating the Deuternomium text into the Pentateuch). At that juncture, all those subject to the will of the Second Jerusalem Temple, including all the inhabitants of the northern Israelite provinces, were being prohibited the right to slaughter for the Passover at home. Everyone was to travel to the temple down south and, consequently obliged to take their meals there. Let us also note that the priestly ritual called for the butchering to occur at sunset with the result that the meal followed its course at night.

There existed – in the light of this hostility between the North and Judah – the most varied of reports to the effect that the Samaritans/North Israelites went to some length at Easter time and the Passover to hinder those who wanted to travel down to Jerusalem and the temple. 4) One such example of attempted interference is described in the NT in Luke 9:52-53. On the occasion of Jesus’ last trip from Galilee to Jerusalem, we read:

“Jesus sent messengers before his face: and they went and entered into a village of the Samaritans to make ready for him. And they did not receive him because his face was as though he would go to Jerusalem.”

It’s striking that Jesus did not chide the Samaritans conduct, aye, he even prevented his disciples of taking revenge. 5) In Samaria – and in a larger sense that means Jesus’ home in Galilee – Passover was a household matter (depending upon the size of the community and the availability of a bull for sacrificial purposes) and the villagers contended vigorously against the prerogatives of the centralized, priestly Passover in Jerusalem. That the Samaritan rejection of the Jerusalem cult was simultaneously directed against the Jewish manner of celebrating the Passover can be gleaned from the report of Flavius Josephus (37 to 100 C.E.). (cf. “Jewish Antiquities,” Book 18, Chapter 2, paragraph 29f.) in the time of proconsul Coponius (6-9 C.E.), that the Samaritans made the celebration of the Passover impossible by secretly scattering bones of the dead in the temple and its environments the preceding evening. This act obliged the priests to declare the cult center therewith impure for the whole week of the Passover. 6)

But the Galileans as well, not only the Samaritans, stood in a certain opposition to Jerusalem. The concept ‘Galilean’ is at the same time synonymous with ‘insurgent’ (zealot, fervor-er) 7) After Jesus’ imprisonment, those searching for Jesus’ disciples refer to them understandably as ‘Galileans’. (Mark 14:70; Luke 13: 13: 1-4; John 7:52.). Jesus, as a Galilean, and in a larger sense, as a Samaritan, resisted Jerusalem’s pre-eminence by celebrating Passover 8) in an entirely non-Jewish, ancient Israelite-pagan, popular folks fashion and, in the course of time, proved himself to be an insurgent, aye, even acting against the Roman occupation forces and Rome’s collaborating Jerusalem priesthood. How precisely Jesus celebrated Passover during the years of his earlier life is unknown to us. We only have the report on his last celebration of the Passover, generally identified among Christians as ‘Holy Communion.’

Even the question of whether or not Jesus celebrated his last Passover on the date stipulated by the Jerusalem priesthood, the 14th of Nisan, the first day of celebration of the unleavened bread, is subject to controversy. In any case there are Christian theologists such as the renowned Adolf von Harnack (1851-1930) who supported the stand that the Maundy on which Jesus celebrated his Passover with his disciples was the day before Passover was scheduled to occur by the Jewish law to occur. 9) Such theologists refer to John 13:1ff. (see H. Haag, Bibel-Lexikon,1951, entry ‘Abendmahl’). Even though John’s gospel, for reasons of a dogmatic nature that have yet to be considered, refers only in passing to a Passover meal without assigning it its extremely important role of instigating the future Christian communion (‘This is my body…This is my blood, etc.’) as in the case of the Matthew, Mark and Luke gospels.

John omits the significance of the meal, but he does instead introduce at that evening the washing of the feet about which Matthew, Mark and Luke know nothing. Despite the peculiarities in John’s gospel (yet to be discussed), the evening of this particular Thursday remains genuinely the correct date since John 13:1 identifies this as “the day before the [Jewish} Passover.” On the basis of what we know about the common, north Israelite aversion, including the Galilean Jesus and his likewise Galilean disciples, to the Jerusalem priesthood in general and against the Jerusalem-centered cult of the Passover in particular, one may assume with substantial likelihood that Jesus and his disciples had no intention of obeying the rituals determined and supervised by the Jerusalem priesthood in respect to both the date and fashion. That is revealed by other, accompanying facts. Regarding the search for an appropriate site where the Passover might be celebrated, Mark 14:13f reports the following:

“So he sendeth forth two of his disciples and saith unto them, Go ye into the city and there shall meet you a man bearing a pitcher of water: follow him. And wheresoever he shall go in, say ye to the goodman of the house, The Master saith, Where is the guestchamber, where I shall eat the Passover with my disciples?'”

Keeping in mind that according to Jewish law, it is rigorously prescribed that the Passover celebration was to be celebrated in the temple courtyard and that a priestly police surely existed to see to it that this prescript was obeyed, then the description of the fashion in which non-residents established contact can not possibly be simply a remarkable accident, but rather the description of Jesus’ conspiratorial modus vivendi. He seeks conspiratorially, together with other like-minded – and that means Galilean-Samaritan-Anti-Jerusalem oriented persons – under cover contact with agents in the city. The two confidents find the owner of the appropriate, secret location, “the day before the (Jewish) Passover,” relying upon an agreed conspiratorial sign. And once the late evening (= darkness) came, Jesus and the Twelve came. (Mark 14:16f). That is to say, the two emissaries initially sent did not belong to the group of the twelve but were two under-cover agents of minor rank drawn from Jesus’ underground movement! After the Passover/ communion, Jesus and his companions withdrew to the Mount of Olives which mean to the open land outside of the city (Matthew 26.30; Mark 14:26).

2. He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish

Another striking indication of the non-Jewish character of the last Passover is the narrated course of this celebration, precisely, the rite of the joint dipping of the twelve into the bowl with their right hands: The Matthew gospel (26:23) has Jesus say, “He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, the same shall betray me” Whereupon Judas, the latter betrayer, asks, “Master is it I?” and Jesus responds, “Thou hast said.” This is a bizarre presentation, for it is extremely unlikely that Jesus would have identified his betrayer without the other disciplines – they’d often flown into a rage before – taking immediate steps to hinder treachery. The Mark gospel, generally judged to be temporally the eldest, presented the matter quite differently and in all probability narrated the events more correctly. In response to the question of the anticipated and expected act of betrayal and its perpetrator from within the ranks of the twelve, Mark writes (14:20): “It is one of the Twelve that dippeth with me in the dish.” In this case, a more easily believable and, at the same time, reasonably appropriate answer is made which does not point a finger at Judas even though he would become the betrayer. Judas does not ask whether he is the malefactor and the answer, ‘Thou hast said’ is superfluous. Similarly the gospel of Luke, universally considered to have appeared after Mark and Matthew, writes (Luke 22.21) “But behold, the hand of him that betrayeth me is with me on the table.”

Here, as well, the future perpetrator remains unrevealed – after all a larger number of hands were placed “with me” on the table – and the name, Judas Iscariot, is not mentioned. But why doesn’t Luke’s text mention the ‘dish’ as does Matthew’s and Mark’s version? This is curious because for the older versions in which the word ‘dish’ occurs must have been known to Luke. We’ll soon learn what goal Luke had in mind when he referred only to “on the table” and not to the ‘dish.’ Behind such discrepancies in the Bible extremely important intent may often be found – as is the case here. Let it be noted that the last, and for that reason in its historical narrative least dependable gospel, John’s gospel (written some time between 110 and 130 C.E.) employed, like Matthew, the tale of Jesus naming Judas the traitor (John 13:21ff.). But John’s gospel avoids reference to the simultaneous dipping of the hand in the dish. Like Luke, he even doesn’t use the word, ‘dish,’ for not to speak of a ‘common dish.’

We can filter out the historical truth from the peculiarities and contradictions involved if we integrate, in accordance with our presentation here, both the historically long suppressed, primeval Passover celebration of the ancient-Semitic, and consequently old-Israelite popular religion which called for the hamstringing of the sacrifice and the efforts, on the other hand, of the hierarchical, Jerusalem-centralized religion of the Law. It is readily apparent that the Galilean/Samaritan Jesus and his associates quite consciously celebrated, not the Passover procedures stipulated by the legal will of the priests, but rather in the context of the primeval Semitic society, built upon tribal structure, feuds and vendettas and which in the context of Passover originally required the ritual of hamstringing (= hobbling, crippling by cutting the bull’s hind leg tendons). When the hamstring was not executed, it was nevertheless virtually and symbolically present with the obeyed custom of not breaking the victim’s bones.

The fashion in which the rite of Passover proceeded in ancient tribal society can hardly be reconstructed from the records drawn together much later under the auspices of the Jerusalem priesthood, for all the texts which would inform us regarding ancient practices against which both the state and its priesthood fought were expunged from the Old Testament. Nevertheless a few scattered bits of text refer back to the archaic hobbling and dismemberment sacrifices do in fact exist. Thus Genesis 49:6 in which the tribes of Simeon and Levi are censured. [We are obliged to turn to the Oxford/Cambridge Version, 1989]. “In anger they killed men, wantonly they hamstrung oxen.” 10)

The word used for ‘hobbling’ (cutting the tendons) in the Hebrew bible is the same word the Arabs have long used as a designation of their hamstringing sacrifice in wartime as a rite for conflict and vendetta, but likewise in celebrating federation and reaffirmation of peace. In Joshua, as well (11:6.9) and 2. Samuel 8:4 the horses of the vanquished, after the victory, are also crippled, while still alive, using the same Hebrew/ Arabian concept, undoubtedly intended as hamstrung sacrifices to celebrate approaching peace. In any case, the point at stake is a wartime situation. Yet two more bible passages deal with dismemberment (that is to say, the total destruction of the creature’s tendons, avoiding – and this is significant – the breaking of bones) as a reaffirming call on the tribe to participate in a vendetta, i.e. Judges 19:29:

“He took a knife and laid hold on his concubine [who had been raped and killed] and divided her, together with her bones, into twelve pieces and sent her into all the coasts of Israel” [as a call to participate in a vendetta]. And in 1 Samuel 11:7, one reads:

“He took a yoke of oxen and hewed them in pieces and sent them [i.e. ‘the pieces’] throughout all the coasts of Israel by the hands of messengers…”[as a call to participate in a holy war].

Irrespective of the vagueness, the lack of precision in these preserved reflections of a former tribal hobbling/Passover, we do find relevant details in the Arabian tradition of conspiracy ‘to the death,’ that is to say in the oath of mutual trust of the perpetrators in the rite of cutting the tendons of the sacrifice in preparation for a tribally sanctified vendetta as well as in a multitude of references to the rite of butchering a sacrifice which involves the cutting of its tendons (or, by occasion, its butchering without the added crippling), combined with the eating of the sacrificial beast from a common dish, all participants simultaneously “dipping their hands into the dish.” Elsewhere, I have listed an imposing number of sources regarding this rite in Arabian literature. (G. Lüling, “Das Passahlamm…als Initiationsritus zu Blutrache und Heiligem Krieg” [= A Passover Lamb…as an initiation ritual in preparation for the vendetta and the holy war], Erlangen: 1982 (=ZRGG 34), 141, footnote 50). See further, W. Atallah in the periodical ARABICA, 20 (1973). His essay is entitled: “Un rituel de serment chez les Arabes” (= the ritual oath among the Arabs: the dipping of the right hand).

An Arab conspiracy to commit oneself, if necessary, to death, unfolds, then, with the eating in common of the Passover/hobbling (Arabic: ‘ta’arqib’ or “ta’aqir,’ i.e. sacrifice of cutting of the tendons) – possibly without carrying the incision out completely, but customarily in conjunction with the rite of eating the sacrifice in accordance with the rite of “dipping one’s hand in the bowl along with the other so involved conspirators.” The rite, and that is fairly certain, originally meant that one is whole heartedly prepared to suffer death itself – as has the sacrificed beast before him – to the end of providing cover and support for his fellows, but additionally, that one believes in resurrection, precisely the symbolic sense of butchering the beast — provided, however, that its bones remain unbroken, unfractured, to enhance the likelihood that it will be resurrected uninjured.

Consider in this context Ezekiel 37:5-6: “Thus saith the Lord God unto these bones; Behold, I will cause breath to enter into you and ye shall live: And I will lay sinews upon you and will bring up flesh upon you and cover you with skin and put breath in you and ye shall live; and ye shall know that I am the Lord.” We have every reason to assume in the light of the hostility of the Galileans/Samaritans to the centralization of the cult of the Jerusalem Passover and the fashion in which Jesus and his disciplines acted, that they, independent from any Jerusalem controls, celebrated the Passover conspiratorially in accordance with the ancient Semitic/Arabic/Old Israelitic hamstringing ceremony, derived from the primeval code of the vendetta and including conspiratorial oaths. That this is precisely the case follows from the conduct of the Jerusalem hierarchy.

The Jerusalem hierarchy had every reason to assume that the primeval practice of hamstringing lived on beneath the surface and might break forth as an eruption of lava, as the initiation rite for a popular uprising at any time. This frightened the members of the hierarchy for they had, after all, the repeated uprising had been initially provoked by the Passover celebrations of the recent past. 11) Precisely the ancient Passover had always been the invitational rite for Vendettas and simultaneously for an uprising. And for this reason, one reads in Matthew 26:5 regarding the question of when the Jerusalem hierarchy will seize and kill Jesus: “Not on the feast day, lest there be an uproar among the people.”

The Passover sacrifice in the Jerusalem temple court was placed under the surveillance of guardians since the time of king Josiah (622 B.C.E.) to enable the king and the state hierarchy of priests to break up the autonomy of the families, kith and kin, clans and tribes in matters dealing with summary, inter-familiar disciplining (without prior confirmation from above) within the confederation and the disinclination of lesser chiefs to obey orders from above in the conduct of war. This autonomy, verily, to one’s death, manifested itself symbolically in the primeval, popular cutting of tendons and the dismembering of sacrifices as rites of covenant and the oaths of brotherly unanimity. The extent to which the secular/priestly central authority feared these plotter’s rite is explicit in the fact that the rite of the “simultaneous-dipping-of-hands-in-the-dish” was verily persecuted inquisitorially: we learn from the Talmud that it was rigorously prescribed in the priestly supervised Passover that those partaking in the meal might not, under any circumstance, eat from a common bowl, but that each was to have his own separate dish – and that has remained the rule up to this very day. 12)

We do not know with absolute certainty whether this prohibition contained in the Talmud was in force in Jesus’ day although this is extremely likely. But in any case, this information regarding the Talmud prohibition of eating from a common bowl, does permits us to conclude that the discrepancies in the four gospels reveal, full well, that the gospel writers were aware of the different meanings of eating from (a) one common bowl or (b) several separate bowls. The earliest of the gospels, the Mark gospel provides the most clear cut and briefest statement (14:20): “He answered and said unto them, ‘It is one of the twelve that dippeth with me in the dish” [i.e. who will betray me]. This statement of Jesus means that one of those who took part in the Passover meal with him and the others and swore allegiance in the most primeval and solemn fashion, even at the cost of his life, will break his holy oath.

In a certain sense this scene is consistent with Jesus’ words to Peter, “Verily I say unto thee that this night, before the cock crow, thou shalt deny me thrice.” (Matthew 26:34 and comparable passages in Luke and John). Here and in the other statements, the gravity of the betrayal is pointed out. The preposterous thought, that the subsequent betrayer, Judas, precisely because he dipped into the bowl along with the others, may be the person to whom Jesus’ words referred, is not present in this oldest version. In the light of what we know about the ancient Semitic rite of dipping one’s hand in the bowl, Mark is simply reporting on the common Passover-hobbling-oath-taking rite of antique Semitic/Arabian/ Old Israelite origins.

The later Luke gospel which softens down its message in other respects as well, tells us (22:21): “But behold, the hand of him that betrayeth me is with me on the table.” Here the thought of designating the betrayer is totally absent. But in the case of Luke, it is quite clear what he is about in avoiding the phrase of “dipping hands in the bowl” in his account of Jesus’ communion with his twelve disciplines, for he sought to suppress any suggestion of swearing an oath – to the death – in a society well acquainted with this practice. He did not want Jesus to appear as one who’d sworn an oath to be fulfilled to the death. This alteration, among many other aberrations, belongs to the efforts of the editors of the New Testament to make Jesus and his followers, after the fact, appear as pacifists.

Matthew 26:23 and John 13:26 serve up the ridiculous tale that Jesus, in the presence of his disciples, designated his future betrayer at the moment that they dipped their hands in common in the bowl or, as an alternative, as he passed on a morsel to Judas. The only thing about these absurd tales that can be sustained is that they prove that the matter of swearing an oath during the communion was in everyone mind at the time and that he, by omitting the word ‘dish’ and the accompanying rites, did away with such aspects of the meeting, and Matthew and John, for precisely this reason, told the fairy tale about the identification of the betrayer, or in other words bleached, dry cleaned and tidied up, more broadly: bowdlerized the whole affair.

Presuming that the matter of “dipping hands in common in the bowl,” was an insignificant detail, a fitful arabesque quite besides the main point, it wasn’t fully expurgated from the gospel while, concurrently, it has never been given close attention in historically oriented, critical theology. The seeming insignificant matter, however, that led to it never being totally excluded from the gospels, provides us with substantial arguments emphasizing the martial character of Jesus’ undertaking: If Jesus and his twelve disciples swore themselves mutually even unto death in the context of this ancient Semitic/ancient Israelitic – and anti-Jewish (!) – rite – and there is no way to get around this conclusion – then logic compels us to accept that not only the disciples, but Jesus as well was prepared to take up arms and fight to kill to protect, as an example, one of his wounded fellows. Jesus celebrated communion after the fashion of the primeval tribal society from which he came.

A crucial determinate in Jesus’ world-view was the uncritical acceptance of life as tragedy, as killing, courage and self-sacrifice, but also of love, aye, even the love of one’s enemies. In this context, Jesus as an avenger or, at least, one ready to so commit himself stands in no way in conflict with the Jesus of love, of self-sacrifice and ennobling admiration for an enemy. For our current society, which attempts to suppress all thoughts of killing while engaging in it wantonly, the rediscovery and appropriate evaluation of Jesus and his followers (a turning back to peg one and the original reality) is a matter of genuinely revolutionary importance. 13)

3. Excurse about the term Baal

At this juncture, it is appropriate to briefly examine the concept BA’AL and its substance particularly in light of the fact that we come across the god Ba’al in ancient Europe among the Germans and Celts. The Semitic Ba’al belongs unquestionable among the type of dieing and resurrected “Gods” (more correctly, a prototype of the “Holy Progenitor” of the archaic cultures). Since this Semitic Ba’al is generally understood as symbolically the dieing and reawakening of nature (Autumn and Spring), he is bagatellized in the scholarly studies of a Christian and Jewish persuasion and treated regularly as a “fertility god” in contradistinction to the Christian-Jewish-Islamic God. This depreciation, however, is quite undeserved, seeing as how Jesus Christ, as well, in the practices of the Christian religion is clearly associated with the seasons and the symbols of fertility (winter solstice, Christmas tree, Easter and its symbols, the Easter egg and the Easter bunny).

Yet an additional, very old, but wrong tradition of the Semitic Ba’al is bagatellised or, more correctly, depreciated and treated with contempt, namely the Bible interpretation that draws a fundamental distinction between the ‘claimed’ landless and unpropertied nomads of Israelite origin, entering into the Holy Land of Canaan, and the propertied Canaanites already resident there. Simultaneously, the Israelite concept of God and that of the hated Canaanite is writ large: on the one hand, a compassionate spiritual God, and on the other hand, a thoroughly materialistic, obtuse (but sexually fertile) god. From this dogmatic, prejudiced attitude towards the Canaanites and their God Ba’al follows the interpretation of what the name means. It is presumed to mean essentially the ‘propertied,’ ‘owner’ in the negative sense of ‘the owner of unjust Mammon (!) as likewise the word Cana’anon, means ‘the land of the business man,’ ‘the merchant.’ But this evaluation of Ba’al as owner’ is through and through false, since the entering Israelites were, in point of fact, not genuine nomads, but rather – like the Canaanite themselves – wealthy, long distant haulers and craftsmen.

The utter foolishness of this judgement over Ba’al as a suspect “propertied citizen” is apparent in the fact that the word did not first appear at this stage of development when “ownership” and “property” had become important. The word is almost certainly much older and arose far back in history at a time when neither word had this meaning. Precisely the fact that Ba’al is a dieing and resurrected “God,” encourages the thought that in primeval times he served as a proto-tribal nomadic prince who gave his life for his “sheep” in a culture that practiced the vendetta. (Theologists are infrequently specialists in Semitics and specialists in Semitics don’t concern themselves with theology.)

But all of this is self-evident when one considers that the root of “ba’al” goes back as far as we can know. In Semitics, the generally agreed three-consonant system of word roots derives from a two-consonant compound to which, in turn, a single consonant is added at the very beginning or at the end – frequently consisting in an adverb particle at the commencement or end or an adjectival or attributive element. When we ask ourselves which element in the fundamentally three consonant sound, “B-’-L” came first in the initial two consonant word and to which the third consonant was added, then only a single construction imposes itself as unavoidable (for reasons that shan’t be detailed here): the three consonant root word arose from the two consonant “B-’” and from it, the consonant “l”. The two-consonant primeval root “B-’,” (without the third consonant ‘L’) means in ancient Arabic – but in our times as well – “to affirm an accepted obligation or contact with a hand shake.” This fundamental meaning leads quite naturally to a situation in which the Arabic “ba’a” means, as a rule, “he buys” (thus past tense “b’ tu” i.e. “I bought” and present tense “yabi’u,” = “I buy”).

But in the beginning it meant simply an affirmation, an assurance, sealed by a handshake, that a promise or a contract will be honoured. In Europe to this day this principle is honoured as a matter of course, particularly among cattlemen. And let it be noted that the English, ‘to buy, bought, bought’ does not derive from the Indo-Germanic languages. In the Oxford Etymology stands: “of unknown origin,” but this is only because one failed to examine the Semitic languages. The word was present in very ancient Europe. In the north, the Semitic word, Ba’al – with no ifs, ands or buts (!) – was present and as a borrowed term in mercantile transactions, also exactly the Semitic verb “ba’al,” meaning ‘buy.’ But this followed quite naturally from its use in ancient Hebrew, i.e. “ba’” meaning in the course of time ‘proprietor,’ ‘owner’ though, in its initial use in the tribal milieu of oath-taking and vendettas, where the legal concept of ‘land’ and ‘property’ did not exist, indeed, it lay beyond conception, the word could have no such meaning. It is not the case that the word ‘Ba’al caused the word ‘Cana’anon’ to mean wealth and commence, but rather the other way around! The word Ba’al acquired its pecuniary favor through it presence in a world of money.

The essential, original, legalistically tribal sense of the Semitic word “ba’a” is clearly apparent in the famous Islamic occurrence of the “bai’at al-Hudaibiya” [sic!], i.e. “the hand shaking at al-Hudaibiya”: when the prophet Muhammad and his followers in the year 6 of the “Hidjra” (628 C. E.), in the village al-Hudaibiya, near Mecca, were obliged to fight for their lives at Mecca with inferior weapons against powerful, well armed adversaries. The contingent of warriors swore before Muhammad, together with his commanders, assembled under a tree, to fight to the death. They passed, man by man, before their admired leader firmly resolved, capping their determination off with the resolute shaking of hands one by one with the Prophet.14) This is the original and essential meaning of the Semitic root of “bai’a” and in its extended three consonant form, “ba’al,” in English, means literally, ‘Sir.’ The word means in principle “he to whom I dedicate myself even unto death with a tenacious shaking of hands.” (The “l” is the common Semitic dative particle.)

The ancient rite of swearing, the “bai’a” (as at al-Hudaibiya), is, in principle the equivalent of the ceremony of fidelity between the anointed leader, Jesus Christ, and his disciples in the context of the Passover-hobbling. (If there is no possibility of performing the communion as prescribed, then the procedure of the “bai’a” takes its place.) In this sense, communion – the essential meaning of the Passover feast of Jesus – is identical with the primeval, ancient Semitic “Ba’al.”

As the boss of a plotting gang, daring to risk his very life to provide an example to the band of his fellow roughnecks, he is the “Ba’a”; that is to say, he is the uncompromising, vengeance-seeking Shepard to whom allegiance is sworn.

4. The belligerant character of Jesus’ movements

The martial character of Jesus’ undertaking has long been discussed in the relevant scholarly literature. It is understandable that institutionally involved Christian theologists are inclined to bagatellize the many, highly differentiated arguments based on the biblical heritage regarding the warlike character of Jesus, holding to the gospels which in themselves attempted urgently to smooth over such details or displace them with contrasting statements to weaken their impact. When Jesus in his missionary, mobilizing effort in Matthew 10: 34 says: “Think not that I am come to send peace on earth; I am come not to send peace, but a sword.” (Compare Luke 22: 36: “He that hath no sword, let him sell his garment, and buy one”), then the gospel writing Matthew – or his later editing ‘correctors’ – also has his Jesus say 26:52 “All they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.”

Confronted with such contradictions, theologists, loyal to their church’s dogmas, take their stand firmly on the side of the pacifist statement and make fun of the ‘seemingly’ warlike facts. In the light of the wealth of historical sources on Jesus’ position via-a-vis the Zealots (the ‘impassionates´), the insurgents fighting against Roman rule and the collaborators in the Jerusalem priesthood 15) , then we, in the context of the present essay, can only encourage the reader to examine the alternate discourses, particularly Martin Hengel (“Die Zeloten,” Leiden/Köln, 1961) and Oscar Cullmann (“Jesus und die Revolutionären seiner Zeit,” 2nd Ed. Tübingen, 1970) to form their own opinion as to whether all this information does not cause one to accept the martial nature of Jesus’ undertaking. From the point of view of those institutionally unattached to the churches, that is to say, independent theologists, profane historians of religion and liberals, opposed to dogmatic thinking, it is fairly clear that Jesus is to be found among those martially opposed to the Roman occupation and the collaborating Jerusalem priesthood. 16)

At the moment, we will limit ourselves here to three conclusions that readily follow from the collected evidence:

1. It is genuinely important that the nicknames of the various disciples of Jesus indicate most explicitly to their involvement with the Zealots, that is to say, with the resistance and underground fighters. That applies to six of Jesus’ twelve disciples by Johannes Lehmann’s counting (cf. his “Geheimnis des Rabbi J,” 1985, page 95ff.). 17) It is altogether proper to do as Joel Carmichael has done, and view the twelve disciples as the captains or Battalion Commanders of Jesus’ forces.

2. Add on to this the fact that although it is determinable that Christian theologists and historians attempted to remove all indications of Jesus’ involvement in the armed resistance movement not only in the case of the gospels, but likewise in the Latin and Greek secular historical writings that appeared in the first century, the less well known work of the Latin historian Sossianus Hierocles, the Praeses of the province of Libanon (Arabia Augustea Libanensis) as of 297 C.E. nevertheless escaped from being expurgated at least in part. Sossianus Hierocles reported that there were 900 “robbers” among Jesus’ followers (Greek: ‘lästäs,’ the contemporary Greek expression for the north Israelite resistance, the term likewise used in the New Terstament to characterize the other two who were crucified together with Jesus). Similar reports are present in the Latin authors, Lactantius as well and finally in a Hebrew source (“Toledoth Jeshu,” a passage in the Hebrew rendering of Flavius Josephus’ “Bellum Judaicum”), which assure us that 2000-armed men accompanied Jesus to the Mount of Olives. 18)

3. Earlier in this text, we have had occasion to note the north Israelite popular religion, the Galilean “pagan cult of the heights” in characterizing the last communion celebrated by Jesus and stressed the fact that this last Passover was an ancient Semitic rite in opposition to the Jewish temple, and consequently, as an anti-Jewish cult in which oaths of bloody vengeance and holy warfare figured, and we identified it as the root of the thought of Jesus and his followers, reaching back over a millennium of anti-Jerusalem, anti-Jewish sentiments in Galilee. 19) This perception of the Galilean-Samaritan-anti-Jewish context of Jesus’ influence has been affirmed in principle by the rabbinic tradition of the two Messiahs, the Messiah ben Joseph and the Messiah ben David. In this framework, the anticipated Messiah ben Joseph was also called the Messiah ben Ephraim.

This indicates that the designation, “Messiah son of Joseph” doesn’t refer to Joseph as the immediate “Father”, of Jesus but rather to the progenitor, Joseph (the most favored son of the twelve sons of Israel’s patriarch, Jacob). In the O. T., this Joseph is, in turn, the father of the sons Ephraim and Manasseh who, again in turn, are the fathers (progenitors) of the two tribes of Ephraim und Manasseh in the context of the ancient Israelite twelve tribes. These two tribes, bracketed together as the tribes of Joseph, however are the most important tribes in the ancient kingdom of North Israel (capital Sichem, later Samaria, ten tribes in all). The ancient southern state, Judah (capital Jerusalem with only two tribes, Judah and Benjamin), existent for a millennium in the time of Jesus, constituted a state in opposition, filled with animosity and resentment.

The Jewish-rabbinic historical tradition knew in this way of a special Messiah for the northern state, hostile to the Jews themselves and centered in Galilee, Samaria and Ephraim, the home of the tribes of Joseph, synonymous with the principle tribes of the north, Ephraim and Manasseh. This Messiah of Ephraim was occasionally also called the “Galilean Messiah.” This Messiah of Joseph or Messiah of Ephraim (we can also say “the Messiah of the Galileans and Samarians”) was hostilely inclined toward the Jews of Judah in the south. In a most revealing sense, he was also designated as the “Messiah of war.” V. Sadek lists the characteristics of this “War-messiah” of the rabbinic, Judaic traditional rabbinic Judaic as follows (“Der Mythus vom Messias, dem Sohne Joseph, Zur Problematik der Entstehung des christlichen Mythus,” Archiv Orientalni 33 (1965), 33.):

a) Relying on his physical strength, the Messiah of Joseph provoked an upheaval

b) But he is but a mortal saviour subject to death and revealing all too human attributes

c) His attempt to achieve a revolution must necessarily lead to defeat in the end, as if doomed by statutory predeterminations

d) His defeat is nevertheless paradoxically simultaneously his victory

e) It leads to the supernatural intervention of God, mediated by the Messiah of David

f) The ultimate uprising, by the agency of the Messiah of David, brings with it the ultimate rehabilitation of the Messiah of Joseph Jesus refused to be seen as the Messiah of David (Mark 12:35-37; compare Matthew 22:41-6 and Luke 20: 41-44) which can be interpreted as meaning that the Galilean Messiah Jesus wishes to have nothing to do with the Jewish Messiah.

King David was a Judean and in his function as king, he subjected the tribes of north Israel to the dominion of Jerusalem, lasting, however, for a relative short period of time, i.e. till the death of David’s son, King Salomo whereupon North Israel separated itself off and sustained its independence from Judah until the prime of Jesus. Still the rabbinic tradition of the two Messiahs, the one of Joseph (= the Messiah of War) and the one of David, in which the Judean Messiah ben David is placed over the north-Israelite (Galilean) Messiah ben Joseph as a consequence of the latter’s defeat, may anyhow be adjudged a product of orthodox-Jewish, that is to say, Jerusalem theology, expressing contempt for the Galilean-Samaritan religious cult of ‘the heights’ and, with it, for its eschatological expectation of the north Israelite Messiah ben Joseph. All of this becomes clearly discernible in rabbinic literature only in the midst of the second century.

Nevertheless my own, highly honoured teacher, Joachim Jeremias, a scholar for the New Testament and Rabbinism, considered it “highly probable that the expectation of a Messiah ben Joseph reaches back well before the Christian era,” calling attention to a passage in the so-called Testament Benjamin, dated back to the second to first century B.C.E. in which stands “You (Joseph) shall fulfil the prophecy of the heavens which declares that he who is above all criticism shall be smeared by the lawless and shall die without sin at the hands of the godless.” Joachim Jeremias believes, “that in the Testamentum Benjamin 3:8, we have in all probability the most ancient evidence of the anticipation of a Messiah from the tribe of Joseph before us.” 20) The Jewish Rabbinic and Arabist, Ch. C. Torrey, likewise argues that the doctrine of the Messiah ben Ephraim “proceeded the Christian era for several centuries.” 21)

In the light of the prophecy in Isaiah 8:23 (possibly dating from the eighth century B.C.E.) which asserts that the Messiah “will raise the Galilee of the pagans to a place of honor” 22) ), it is highly likely that Galilee and Samaria followed a pathway or several paths, quite different from Judah throughout their history and anticipated in the course of the coming millennium an ultimate Messianic final age in accordance with ancient north Israelite, i.e. ‘pagan’ (the cult of ‘the heights’ and the Messiah) and Ba’al-like tribal norms. After all, the motif, the Messiah, is an essential element in the ‘cult of the heights’ and refers to the resurrection and return of the king of the primeval, mythic past of the northern state of Israel. Consider the fantastic, indeed rabid, means to which the Jerusalem priesthood of the southern state of Judah took recourse to root out the ancient Israelitic cult of ancestor worship and graves erected “in the heights” on the pretext of realizing a Mosaic centralization of cult activities (II Kings, 23: 4-20; V Moses 12: 1-3).

Let it be noted with the wisdom of hindsight that the Jews of the southern state, in their efforts to force themselves upon the northern state, unrelentingly and recklessly, severed themselves off from the course of events that eventually led on to the rise of Christianity with its Galilean Messiah. In essence, this occurred centuries before the later consummation was actually effected. Even the fabled tale of the origins of the Passover which the Judeans invented – that is to say, that Passover was founded at Jahwe’s initiative on the occasion of the later invented departure of Israel from Egypt, a proposition leading the Jews to this very day to celebrate a pure invention rather than the celebration of the primeval oath to the tribe’s leader to fight ‘to the death’ in vendettas against the enemies – even this belongs in the complex.

Radically stated, the separation of the Jews from the ancient Semitic, ancient Israelite religious tradition (beginning in the seventh and sixth centuries B.C.E,) may be seen as the commencement of the separation of Jews and Christians – this despite the fact that the latter, in an organized, literal sense, came only long after.

Let it be further noted in passing, that the dominating concept of two Messiahs, one of them an Aaronite or priestly being, the other a profane David-like personage, as they appear in the Qumran texts of approximately the time of Jesus have nothing whatever to do with the two Messiahs, i.e. the north Israelite Messiah of War, ben Ephhraim and the Messiah of peace, ben David, in the rabbinic tradition. 23) The warlike Messiah ben Joseph is a product of Samaritan-Galilean thinking and therefore heretical for Orthodox Judaism while the Jewish personage of the Messiah ben David consummates the ultimate stage of history’s unfolding, seeking harmonization. 24)

The two Messiahs in the Qumran text, the one an aaronite-priestly the other the profane David, are a purely inner Jewish affair, which has nothing to do with Jesus. The current fad of interrelating the Qumran texts as closely as possible with Jesus are for this very reason mistaken. Current Christian theology prefers, where ever possible, to busy itself with the concept of the two Messiah in the Qumran texts and avoid considering the thought that the rabbinic tradition of the War Messiah ben Joseph and the Christian tradition of the Messiah Jesus ben Joseph “can be two variants of an original myth.” “That no researcher in the New Testament – as far as we know – has succeeded in reaching this conclusion,” to cite V. Sadek (ArOr, 33. 33f.), is a result of Christian theologist’s efforts to treat Jesus as quite distant from any form of martial activity – as is already clearly apparent even within the gospels themselves.

In the light of the repeated efforts at pacifistically retouching in the gospels, one should move on and consider the person of the ‘carpenter Joseph,’ the claimed father of Jesus, as an invention, derived from the tribal name, Joseph, behind which lies the concept of the warrior Messiah, ben Joseph. Such a derived invention would add but yet one more detail, indicating once again the martial character of the Messiah ben Joseph. After all, the preoccupation with the Jewish Qumran texts, on the one hand, and the silence of Christian theologists regarding the Galilean War Messiah 25) , on the other, is decisive – once the Christian Church had integrated the Jewish OT into its Canon of Holy Scriptures and the genuine writings on Jesus had been banished to the Apocrypha – to repeat: the preoccupation with the Qumran texts is decisive in generating a vested interest within the Church to prefer the image of Jesus as an orthodox Jew rather than seeing him, in the historically much more likely construction of events, as a representative of – in Jesus’ own time- a thousand year old north Israelite, heretical opposition against the hierarchically ordered Judaism of priestly/rabbinic Jerusalem.

It is very much to the point, following the number of arguments brought forth for the martial character of the movement of the Messiah ben Joseph, named Jesus, to bring this discussion to an end with the extraordinary observation of the late English historian of religion, S.G.F. Brandon, the translator of Martin Werner’s “Die Entstehung des Christlichen Dogmas” into English and, himself, the author of “Jesus and the Zealots,” Manchester, UP (1967). He writes there, page 320: “It is well to remember that Christian tradition has preserved, in the Apocalypse of John, the memory of another, and doubtless more Primitive, conception of Christ – of the terrible Rider on the White Horse, whose eyes are like a flame of fire…He is clad in a robe dipped in blood, and the name by which he is called is The Word of God… From his mouth issues a sharp sword with which to smite the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron; he will tread the wine press 26) of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has a name inscribed, King of kings and Lord of lords.” 27)

It must be pointed out with emphasis that the military movement of Jesus and his supporters is radically distinct and in a sense heavenly removed from the Jewish warriors of his own time, set upon throwing off the yoke of alien roman rule and the re-erecting of a sovereign worldly national state of Judah dominated by theocratic priests. Jesus and his supporters are not liegemen of the orthodox-priestly, Jewish Old Testament, but rather of the northern Israelitic, popular-heretical cult of (a) the Messiah and (b) the graves ‘in the heights,’ and for this reason, of (c) books dealing with the Apocalypse, the “earth’s anticipated ultimate days,” particularly the Henoch Apocalypes 28) ) and, in accordance with such prophetic literature, they look forward to the resurrection of the Messiah, Jesus ben Joseph, who had died a sacrificial death in combat, and with him to God’s kingdom that will rule ever after on earth. The traditional, earthly future of Jerusalem and the Jewish state was a matter of utter indifference to them.

Jesus and his faithful fought, not for the liberation of a mundane Israelite empire. Jesus and his mundane struggle is a tantalizing and accordingly indispensably sacred holy drama that has to be played out to the end so that the empire of God may expand out over the earth. This primeval concept of the fight against Rome and its Jewish collaborators (decidedly not for a unexceptional, run-of-the-mill priestly Judah) as an unavoidable, apocalyptic drama, to precede God’s appearance, meant that the earliest Christian standpoint clashed head-on with the intents and goals of the struggle of insurrections to cast down the yoke of alien domination to the end of re-establishing an earthly Jewish state with its national cult of the temple.

Footnotes

1) Cf. as an example, the provocative, detailed article of the theologian Gerd Theissen, “Aporien im Umgang mit den Antijudaismen des Neuen Testaments”, Festschrift für Rolf Rendtorff, Neukirchen-Vluyn (1999) 535-553. His essential proposition: “The temple criticism reaches back into the time of Jesus, when he and his supporters organize an ìnter-Jewish movement for renewal.” Theissen leaves the thousand-year-old hostility between North Israel (Samaria and Galilee) and the southern Judah entirely to the side even though the Galilean Jesus quite unmistakably persists in affirming the ancient hostility and its religious traditions. The Jesus movement was always beyond the pale of Judaism and constituted an intensification of that opposition to Judaica. Back to the text

2) A parallel to the proto-Christian epithet of calling the Jews the children of the devil (cf. John 8:43-44). As for Jesus as a Samaritan, cf. Robert Eisler, “Jesus Besileus ou Basileusas,” (1929), I, 178; H. Hammer, “Traktat vom Samaritanermessias. Studien zur Frage der Existenz und Abstammung Jesus,” Bonn 1913; Tertullian, “De spectaculis,” ed. A. Reifferscheidt u. G. Wissowa. Quinti Septimi Florentii Tertulliani Opera, I, Prag-Wien-Leipzig, 1890, 28 u. Kap. 30 “Jesus der Samaritaner” and R. Myer, “Der Prophet aus Galiläa. Studie zum Jesusbild der drei ersten Evangelien,” Leipzig, 1940. Back to the text

3) The judgement of Rabbi Jochanan ben Zakkai (died ca. 80 C.E., cited by Strack-Billerbeck, 5th edition, volume I. 157) “Galilee, Galilee, You have received the law [meaning the Jewish Old Testament]; In the end, you’ll be nothing but robbers.” His words are applicable, not only to Jesus’ time, but for the total thousand year period of Galilee history. In passing let me note that the word Galilee means ‘the land of the stone circles, which is to say: the land of the ancient megalith culture and its belief in resurrection, a matter that will concern us further below. Back to the text

4) With regard to the interfering Samaritans, when pilgrims travelled south at celebration times, cf. Martin Noth, “Geschichte Israels,” 6th edition, Göttingen (1966), 388 Back to the text

5) Helmut Merkel makes the point quite well, writing, “When Jesus, in a surely authentic parable of the ‘compassionate Samaritan’ (Luke 10:30ff.), allows no one but a Samarian to have performed this act of grandiose humanity, any patriotic Jew would consider this an affront.” (Cf. H. Merkel, “The Opposition between Jesus and Judaism,” in Ernst Bammel and C.F.D. Moule, eds., “Jesus and the Politics of His Day,” Cambridge CUP (1984), 129-144, spez. 136 Back to the text

6) Consider H.G. Kippenberg, “Garizim and Synagoge,” Berlin/New York (1971), 95. From Josephus’ report, it also followed that the Samaritans themselves, seeing their admiration for the cult of the dead and their cult of reliquaries ‘in the heights,’ did not view the bones as causing impurity, while the Jews, in particular the Sadducees, emphatically rejected any kind of death cult and responded with religious persecution against the popular worship of forbearers, heroes or a cult of a Messiah. Precisely this lies behind the indignation of every Jew when confronted with the Christian cult of holy relic, including even entire skeletons. Back to the text

7) cf. Martin Hengel, “Die Zeloten,” 1961, 1961, 56-60 and Rudolf Augstein, “Jesus Menschensohn” (1974), 32f together with the latter’s recommended literature. Back to the text

8) On the contrast between the Judaic and ‘pagan’ Samaritanism, cf. Johann Wilhelm Rothstein, “Juden und Samaritaner, Die grundlegende Scheidung von Judentum und Heidentum. Eine kritische Studie zum Buch Haggai” (Beiträge z. Wiss. v. AT, 3), Leipzig, 1908 Back to the text

9) Regarding the deviate Passover date, cf. J. Lehmann, “Das Geheimnis des Rabbi J.,” 1985, 92 Back to the text

10) This archaic verse contains a Parallelismus membrorum (parallelism of verse’s halves). That is to say, the first half says precisely the same thing as the latter half with the consequence that literal translations would be: in order to kill a man in anger, one first crippled an Oxen. [King James’ liegemen wilfully manipulated the text above, writing “In anger they slew a man (singular!) and in their self-will, they digged down a wall (!).”] Back to the text

11) Cf. Robert Eisler, “Jesus Basileusas, (Vol. 1, 1929; Vol. 2, Heidelberg (1930), 476 with the note 9 (On uprising during Passover in the years 4 BCE and 2 CE and likewise Martin Hengel, “Die Zeloten,” 1961, 331 and 363 and Rudolf Augstein, “Jesus Menschensohn, 1974, 32f. Back to the text

12) Cf for this Strack = Billerbeck, “Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud mit Midrasch,” Muenchen (1956), 2ed., Volkulme I, Page 989 & Vol. IV, I, Page 65f; Rudolf Augstein, “Jesus Menschensohn,” RRR – TB – Hamburg (1974), Page 120. Back to the text

13) On the concept, ‘Post-Jesusanic ‘Christian,’ compounded from the Old Israelite and the last Passover of Christ, cf. the present author’s essay, “Preconditions for the scholarly criticism of the Koran and Islam” in the ‘Journal of Higher Criticism’, Vol. 3 (1996), page 103ff. Back to the text

14) Cf. Frantz Buhl, “Das Leben Muhammads,” German translation by H. H. Schaeder, Leipzig (1950), page 286ff. Back to the text

15) One must take care to note that extremely divergent groups were active at that time, namely the resistance from among the Samaritans and Galileans, who were opposed both to the Romans aliens and also against the Jerusalem priesthood, but there was also a Jewish nationalist resistance which opposed foreign rule while being loyal to the Jewish state and sought to re-establish a Jewish empire.Back to the text

16) In Karl Kautsky’s “Der Ursprung des Christentum,” 14th ed., Berlin 1926, cf. the section, 384-391, “Das Rebellentum Jesu.” Further James Rendel Harris, “The Twelve Apostles,” Cambridge 1927; Robert Eisler, “Jesus – Basileus ou Basileusas; Die messianische Unabhängigkeitsbewegung vom Auftreten Johannes des Täufers bis zum Untergang Jakobs des Gerechten, 2 Vol. Heidelberg 1928-1930; Robert Eisler, “The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist, New York 1931; Ellis E. Jensen, “The First Century Controversy over Jesus as a Revolutionary Figure,” JBL 6, p. 261-272; Joel Carmichael, “Leben und Tod Jesu von Nazareth,” München 1965; Samuel G. F. Brandon, “The Fall of Jerusalem and the Christian Church,” London, 1951; S. G. F. Brandon, “Jesus and the Zealots,” Manchester 1967; Ernst Bammel und C. F.D. Moule (eds), “Jesus and the Politics of His Day,” Cambridge UP 1984 which includes a number of relevant essays, among them a historical survey regarding E. Bammel’s “The Revolution Theory from Reimarus to Brandon,” pages 11-68; Johannes Lehmann, “Das Geheimnis des Rabbi J. ;Was die Urchristen versteckten, verfälschten und vertuschten.” Hamburg-Zürich 1985. Back to the text

17) Consult C. Daniel, “Esséniens, Zélotes et Sicaires et leur mention par paronymie dans le N. T.,” Numen 13 (1966) ; Martin Hengel, “Die Zeloten, ” 1961, 344, note 5 which refers to J. Rendel Harris, ” The Twelve Apostles, ” 1927, 34, note 1 ; S. G. F. Brandon, “The Fall of Jerusalem, ” 1951, 106. Back to the text

18) Consult Robert Eisler, “The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist,” New York, 1931, 370 where further sources are named. Back to the text

19) More on the unruly, political-religious history of Galilee is offered in Johannes Herrmann, “Galiläische Probleme,” Die Welt als Geschichte, 7 (1941) 234-241 Back to the text

20) To elaborate the discussion and other relevant literature regarding a pre-Christian origin of this tradition, cf. J. Jeremias, ThWNT (= Theologisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament), Vol. V, 685 together with footnote 243 and Rudolf Augstein, “Jesus Menschensohn,” München-Gütersloh-Wien 1972, 32ff together with the footnotes 73-78. Additionally Martin Hengel, “Die Zeloten,” 1961, 304f. Back to the text

21) Ch. C. Torrey, “The Messiah Son of Ephraim”, JBL (=Journal of Biblical Literature), 66 (1947), 253-277, particularly 255. Additionally Heinz-Wolfgang , “Die beiden Messias in den Qumrantexten und die Messiasvorstellung in der rabbinischen Literatur,” ZAW (=Zeitschrft für Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft), 70 (1958), 200-208, particularly 20ff. Back to the text

22) The above citation is expurgated (!) from the ‘King James Version,’ only incompletely suggested in “The Revised English Bible,” Oxford/Cambridge, 1989, but intact in the German language Herder version, 1980, superintended by the Katholische Bibelanstalt GmbH, Stuttgart Back to the text

23) Heinz-Wolfgang Kuhn agrees, writing, “that the concept of placing a warlike Messiah ben Joseph next to a Messiah ben David as occurring in the rabbinic tradition, has nothing whatsoever to do with the two Messiahs in the Qumran texts.” Page 205. Cf. “Die beiden Messias in den Qumrantexten und die Messias-vorstellung in der rabbinischen literasture,” ZAW 70 (1958), 200-208 Back to the text

24) For J. Heller, whose Dissertation, “Die Efraimitische Messias-Tradition,” of 1951 which never appeared in printed form, sees it correctly. The war Messiah, ben Joseph is “the Judaic transformed …type of the north Israelite or efraimite kings.” Cited in V. Sadek, ArOr 33, 1965, 34 Back to the text

25) Even the compendium, edited by E. Bammel and C.F.D. Moule, “Jesus and the Politics of His Day,” Cambridge (1984), pp. 511, remains uniformly silent regarding the Martial Messiah ben Joseph, not touching upon him in the course of the extended scholarly discussion. Back to the text

26) Isaiah 63: 3: “I have trodden the winepress alone; and of the people there was none with me: for I tread them in mine anger and trample them in my fury and their blood shall be sprinkled upon my garments and I will stain all my raiment.”Back to the text

27) Brandon drew richly from a modern theological literature in which those cited are uniformly of the opinion that this statement in the Revelations of John refers to Jesus. Back to the text

28) Differentiating between ‘Israelite,’ i.e. that legacy evolved in the north in Galilee and Samaria and ‘Jewish,’ i.e. the region controlled in the environs from Jerusalem, Martin Werner sees Jesus’ oppositional attitude towards the Jewish Old Testament as following from the centrality of the ‘Israelite’ Apocalypse reflected outwardly in the apocalyptic frame of mind he himself assumes. One must bear in mind that this Apocalypse constituted the essence of primeval, written Christian canons. Once the nascent Hellenistic church, still in the process of organizing itself, determined that the apocalyptic end of the world and the descent of God’s empire from the firmament was not taking place – that is to say that which Jesus and his followers preached – they dispensed with this tradition in toto, shoved it off from them, after they themselves having been rejected by the Jews. Only in the canon of the Ethiopian Church was Apocalypes of Henoch, the so-called “Book of Jesus’ Faith,” conserved, though, there as well, it failed to win influence once its revelations failed to materialize. (cf Martin Werner, “Die Entstehung d. christl. Dogmas,” 2nd Edition, 1954, 144ff.) Back to the text

Translation by Dr. Michael Conley

[Dr. Conley’s website is: www.thecosmiccontext.de]