An Introduction to Chronology Criticism

Intermediate results of research

Using books written about this topic during the past few decades, in summary here are the most important points:

Human history has been fragmented by recurring catastrophes that destroyed the respective level of civilization, setting humanity back by entire epochs of time. Such cosmic collapses, “jolts” in the solar system, were often reported, but also hushed up and so became an unprocessed trauma.

After these collapses, researchers and philosophers tried unsuccessfully to piece together meaningful fragments of history. Somehow this mosaic became generally valid, even if a number of inconsistencies were noticeable. After the researchers and pioneers of historiography in the “Renaissance”, their descendants defend – against better judgment – this structure became an independent literary construction.

The foundations of this construction are weak, they are imaginary and often pure speculation. By contrast, our new theories of world historiography have been developed and matured over decades after deep consideration, discussion and with sometimes contradictory publications. The view of our research subject has changed over time in the light of new evidence, as it should; Our conclusion is: there no longer remains any fixed framework.

Reliance on the birthdate of Jesus- once the anchor for the entire chronology – has long proved untenable. The assumption that some catastrophe, a “big jolt” around 650 years ago, changed the earth’s surface and its position in space, causing all subsequent repopulations, conquests and discoveries of new coasts and lands by seafarers (Portuguese, Spanish or English), explains many gaps in understanding. The church’s missionary activities contributed very much, too.

This processes produced chronology from the end of the 15th century to the 18th century. It shows agreement emerging as an ever-converging timeline. This was to be expected, so today all educated inhabitants of the globe have adopted the uniform conception of history that largely goes back to the fantasies of the Old Testament.

According to popular belief, our year count was created by the monk Dionysius Exiguus around 1,500 years ago, for whom the year 1 of the birth of Christ lay 532 years before. In our opinion, this method of counting is not older than 500 years and began in 1519 at the coronation of Emperor Charles V (the Holy Roman Emperor), becoming common usage throughout Europe by 1700.

According to Catholic opinion, the Vatican used the Spanish provincial ERA from around 1443, but this is a later construction and untrue; the entire historiography of the period before 1500 AD presents itself as a novel, with the heroic figures Moses, Jesus, Paul and Mohammed all fictional.

If one tries to derive missing centuries from these constructs, this is impossible due to their structure. Whether 300 or 700 or even a thousand years were skipped in the new construction is irrelevant. Such work belongs to literary criticism, not to historiography. After the Gregorian calendar reform in 1582, the numerical structure became consolidated, setting around 1,500 years between the Peace of Emperor Caesar Augustus, (the fictional time of birth for Jesus) and the “Cinquecento”, the period between 1500-1599 AD.

In the early Renaissance people had other ideas, as can be seen from the Comentarii by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455) and Leonardo Bruni from Arezzo (1370-1444); also writers such as Petrarch, Alberti and Vasari: It was believed that between the fall of Rome (410 AD is usually considered the fixed date) and the reawakening of antiquity (i.e. around 1400) only around 700 years passed, i.e. around 300 years less than assumed today (presented detailed by Siepe 1998).

Efforts were made to find clues to realistic chronology in every possible way. One author who tried to reconcile the Old Testament’s generational register with astronomical calculations was the Provençal Catholic Nostradamus (1503-66); in a letter to his son, he flatly declared the time given by the pagan Varro as incorrect and used his own method setting a beginning of the year count: 4173 BC was the first year of Adam.

The Protestant theologian Joseph Scaliger (1540-1609), son of the famous philologist Julius Scaliger, wrote in response to Pope Gregory’s Calendar Reform a work De emendatione temporum (Improvement of the Calculation of Time; Frankfurt am Main 1583), in which he proposed a new chronology, deviating only minimally from Catholic ideas; it became established over the next few decades. His final work, Thesaurus temporum from 1606, became common knowledge fifty years later as historiography, determining our current ideas and only to be improved in tiny details. The tables at the end of that book are taught in schools until today. Ever since then, Scaliger has been considered the father of the new chronology.

How did the Greek idea of history fit in?

The attempt to combine Biblical and Greek history presented a great difficulty because like two series of novels, written separately, they were difficult to reconcile. First of all, a data framework for Greek history had to be created to be compared with the Biblical patriarchs. For this purpose, Scaliger’s friend Casaubonus, who had already “discovered” (rather forged) ancient manuscripts, found in Paris in 1605 a list engraved in copper on which the winners of Olympics were named from the beginning up to the 249th Olympiad, a period spanning exactly 1000 years. Such a long list would suffice, since it joins a corresponding list of all the Roman consuls.

Scaliger then added kingdom lists from Peloponnese, Attica and Macedonia to these Olympians, following with the king list of Manetho contained in Eusebius (or rather Synkellos) and lists of rulers from the Orient. The extent to which existing oriental models, such as Armenian or Syrian texts, were used or whether they were only introduced later (by the church?), is an investigation for skilled forensic experts. These contents were so carelessly invented that there remains no doubt about this imaginary literary ‘foundation’.

Nevertheless: The overall framework of the chronology of world history remains based on these inventions; it cannot be overthrown and no new reliable framework can replace it.

During this time, not all contemporaries did agree with this chronological monstrosity. One of the clearest-thinking men of the Enlightenment Age, Isaac Newton (1643-1727), resisted this calculation of time for decades and used theological considerations to claim that the historical dates compiled at the time were several centuries too high. In his opinion, the most important dates in classical Greek history should be brought closer to us by at least 300 years, perhaps even 500 years. Newton’s arguments were as fantastic as they were baseless, so they were rightly ignored.

The equally artificial data of his opponents were different. Public discussion in the 18th century shows that the data put forward by Scaliger and Pétau were purely artificial products. The fact that they are believed as true today is grotesque.

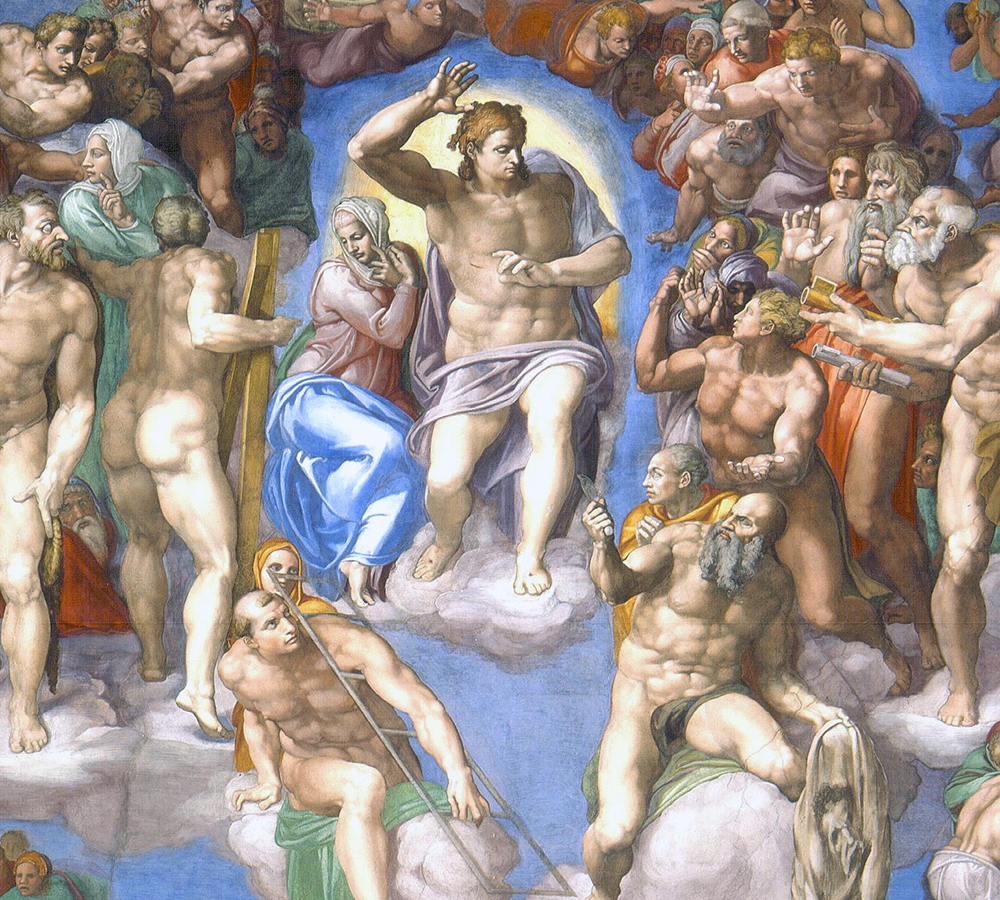

The Work of Computists (ERA) “The Last Judgment”

An intermediate stage halfway between fabricated history and the targeted creation of a number system for the course of history is preserved in the work of the Computists.

The central point playing the guiding role in these Christian efforts to develop their own chronology, was the calculation of the end of the world. The question of how much time has passed since the world was created directly relates to the question of how long the world will last: When will the Last Judgment occur?

Isaac Newton also grappled with this question. In addition to knowledge of the Bible- Newton learnt Hebrew for this purpose- the methods primarily involved astronomical calculations. Of course, we no longer need to bother with this question today – although the recent hype around the year 2000 or 2001 (or 2012!) was not free of such irrational ideas. Nevertheless, we include this religious motivation as a guideline for the efforts of the late medieval chroniclers, because the result- our current chronology- is shaped by the world of ideas at that time.

The motivation for Christians to introduce a consistent yearcounting method was derived from the Iranian calculation of the age of the world: 6,000 years after the creation of the world, the end of the world was to occur through Saoshyant, the Saviour. The Jews adopted this obsession from the Persians and expanded it further in their apocalyptic writings and by this way the expectation of the future end penetrated into the Christian world of faith, first banally as “imminent expectation of the Messiah”, then as cryptic feature and theological subtlety, still paramount even in Newton’s time. The monks involved in calculating the history of salvation were called computists creating schematic time tables in which packages of years occurred that had deep symbolic meaning.

All of this would seem no more than a curiosity today if the annual figures developed from it were not still contained in our time tables. ERA 666 is considered the centre of this period (because of Rev. John 13, 18). You have to read it six-six-six, including 369 (three-six-nine) and 963 (nine-six-three) as symmetrical numbers which from a computational point of view, are equivalent. The gap between them is 297 years, itself a magical number, the product of the important prime number 11 and the three to the power of three (= 27) an expression of the Trinity.

If you subtract 44 – the postulated date of the first Julian calendar reform (44 BC) – you get the value 622 instead of 666 (today beginning of the Islamic calendar Hegira, Hejra). And so for 369, -44 = 325, the first worldwide council of the Church (Nicaea), and 963 – 44 makes 911, beginning of the empire. And so on, a multitude of years still memorised in school today. It seems that this fabrication of one’s own history or that of one’s opponent was a widespread pastime in the Renaissance.

For Spain I would like to mention three names that can represent the secular part of the “action”: Pedro de Medina, Juan de Viterbo and Gerónimo de la Concepción. They wrote history books and geography works that seemed so real and were so well thought that I fell for them for several years (1977, Chapter 22). The sources they use must be exceptionally good because many of their claims can now be proven archaeologically in the field. But that doesn’t make their “Chronicles” realistic. The king lists of Iberian prehistory were as invented as those of the Greeks, Romans and Chaldean kings. They had preserved amazing knowledge from antiquity and scored many direct hits. Nevertheless: The order, all dates and proper names of these “rulers” are pure fantasy.

What remains of this colourfully woven carpet, (as Clement of Alexandria called his historiographical work) when we recognise the historical background as useless? A fantastic image of the Renaissance, an exuberant creative power that in many ways created a self-confidence that made our current cultural heights possible. In other words: After the first disappointment – just a disappointment – I see no reason to condemn or despise the “great action” of rewriting history. I just want to see how it all came about and how it has shaped us to this day.

Christianisation

This refers to the unexplainable process that in a few generations, perhaps a hundred years, many tribes and peoples adopted Christianity, sometimes even making it the only religion as in Spain, for example. This has never been explained. Our chronology-critical approach, in which written history is viewed only as religious literature, says:

Any historiography based only on “holy books” or writings dependent in turn on them, has no basis whatsoever unless supported by inscriptions or similar impeccable evidence. This means that it is unreasonable to go back past the 1500 mark. The countless manuscripts in Hebrew and all the other languages of the Near East are not eradicated, but their value for real history and chronology is reduced to an appropriate level near zero.

When we read how Lot generates two new tribes with his daughters after the cities were destroyed, we remember that this pattern occurs in many collections of legends and does not describe any historical process. Certainly no process essential to our origins. We live in an enlightened age and have ‘known’ this for a long time. There remains contradiction between the knowledge of the educated and the consciousness of the masses. Any “story” that appears in the dictionaries about the introduction of the chronology “after the birth of Christ” is irrelevant for ‘history’. Dionysius may have lived at some time; yet it is not his calculation that we follow today, but an invention implemented a thousand imaginary years later, in the 16th century, with the introduction of the Gregorian calendar worldwide from the 17th to the 21st centuries.

What’s left?

Nevertheless a question remains: How long is the gap between the fall of the Roman Empire and the resurrection of civilisation (we call the “Renaissance”)? If the philosophers of modern times do not agree on this- nor even 500 years ago – because no time interval was known, how could we or others find out?

Ptolemy’s Almagest (2nd century AD) incorporates Christian numerical symbolism into his era thus bringing it close to the Renaissance. Arabs using and translating these texts and tables (such as Battani) viewed these not as observations from 800 years ago but as information relevant to their time (see my “Year Cross”, Part 8).

Something strange happened: the precession had varied over time and the sky had moved erratically. From the changing precession dates and the incomprehensible trepidation values (“the tremor”) it became clear that a constant course of earth movement could not be expected. There were more than 700 years between Eudoxus and the entries in his star atlas, an unthinkable time gap that can only be explained by a jump. If the earth jumps, also evident from other astronomical and calendar data, the last tool for determining time is no longer valid. Newton’s values are as speculative as his entire “calculations”, which turns out to be 500 years shorter than would be deduced from the legendary traditions.

The only thought left for us was that a reliable calculation of the time courses is impossible because jumps in precession distort the picture.

Nevertheless, we have designed a diagram providing an approximate clearer idea of these periods. Apart from knowing the cause of these precession jumps has not (yet) been found- and plays no role in our considerations- these are the characteristics of the last jumps: They always take place in the direction of the constant precession, not against it; some calendar days were skipped. These jumps caused immense damage to the earth’s surface. The destruction of human civilisation is the reason for our inability to estimate the length of time that has passed between leaps, not even in the range of 300 or 500 or 700 years, or a millennium.

The emergence of monotheistic religions is closely linked to these leaps which may have hindered serious engagement with the purely mathematical aspects of jumps in the past. This is excluded from the chronology-critical work.

I quote from “Jahrkreuz”, p. 445):

“If we want to describe our history as an actual passage of time, we cannot start the count at any mythical beginning, as customary in the past, for example with the creation of the world or the new beginning after a Great Flood, the first Olympiad or the founding of Rome, death of Alexander or birth of Jesus Christ. All we can do is step backwards from today and see how far we can get. All documents must be critically examined to determine when our oldest records bear reliable dates. As far as our year count goes, that’s around 1500 AD (plus minus 20 years). Everything that comes before is “protohistory” in this sense of the definition, and we have to let those experts speak who have worked archaeologically and dated their finds without historiographical guidelines. This way of working is rare so far.”

References

Däppen, Christoph (2004): Nostradamus und das Rätsel der Weltzeitalter (Zürich)

Grotefend, H.: Zeitrechnung des Deutschen Mittelalters und der Neuzeit (Hannover 1891–1892/98)

Siepe, Ursula und Franz (1998): „Wußte Ghiberti von der ‚Phantomzeit‘? Beobachtungen zur Geschichtsschreibung der frühen Renaissance“ in: Zeitensprünge 2, 1998, Mantis-Verlag, Gräfelfing bei München, S. 305-319

Topper, Uwe (1998): Die Große Aktion (Tübingen) (download as pdf)

Topper, Uwe: Kalendersprung (Tübingen 2006, S. 370)

Topper, Uwe (2016) : Jahrkreuz (Tübingen)

[24.11.23]

Translated into English by Rainer Schmidt

One Comment

Nick Weech

“Each of the three biblical religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, exhibit lacunas of 200 to 250 years in the phases of the development of their canons of Holy Scriptures. Critical minds have always conjectured that behind these lacunas lie fundamental distortions of the original religious intentions of their founders and their communities.”

The recent article re: A new paradigm needs to address this question first. Why is there such confusion? Maybe the order of precedence of the three is at the bottom of this?

[I’m unable to comment on that post itself.]

As you say, above, and have said for many, many years:

“For Spain I would like to mention three names that can represent the secular part of the “action”: Pedro de Medina, Juan de Viterbo and Gerónimo de la Concepción. They wrote history books and geography works that seemed so real and were so well thought that I fell for them for several years (1977, Chapter 22). The sources they use must be exceptionally good because many of their claims can now be proven archaeologically in the field. But that doesn’t make their “Chronicles” realistic. The king lists of Iberian prehistory were as invented as those of the Greeks, Romans and Chaldean kings. They had preserved amazing knowledge from antiquity and scored many direct hits. Nevertheless: The order, all dates and proper names of these “rulers” are pure fantasy.”