Easter Dates in an Inscription at Périgueux

Easter dates in an inscription in the old cathedral of Périgueux – who designed them and when ?

In summer 2010 I visited the town of Périgueux in Western France in search of a mysterious inscription in a church showing about 90 dates of Easter in the Early Middle Ages. It was Dr. Ulrich Voigt who had heard of this inscription and notified me. As this artefact can be decisive in determining dates more than a millennium ago, I was eager to see it.

Publications were scarce and contradicting. I mainly used:

Cordoliani, Alfred (1961) :”La table pascale de Périgueux”, in: Cahiers de civilisation médiévale 4 (1961) 57 – 60.

Corpus des Inscriptions de la France méditerranéen (1979) t.5 : Dordogne, Gironde (Univ. de Poitiers, Centre d’Ètude superieure de Civilisation méditerraneen, avec l’aide du CNRS)

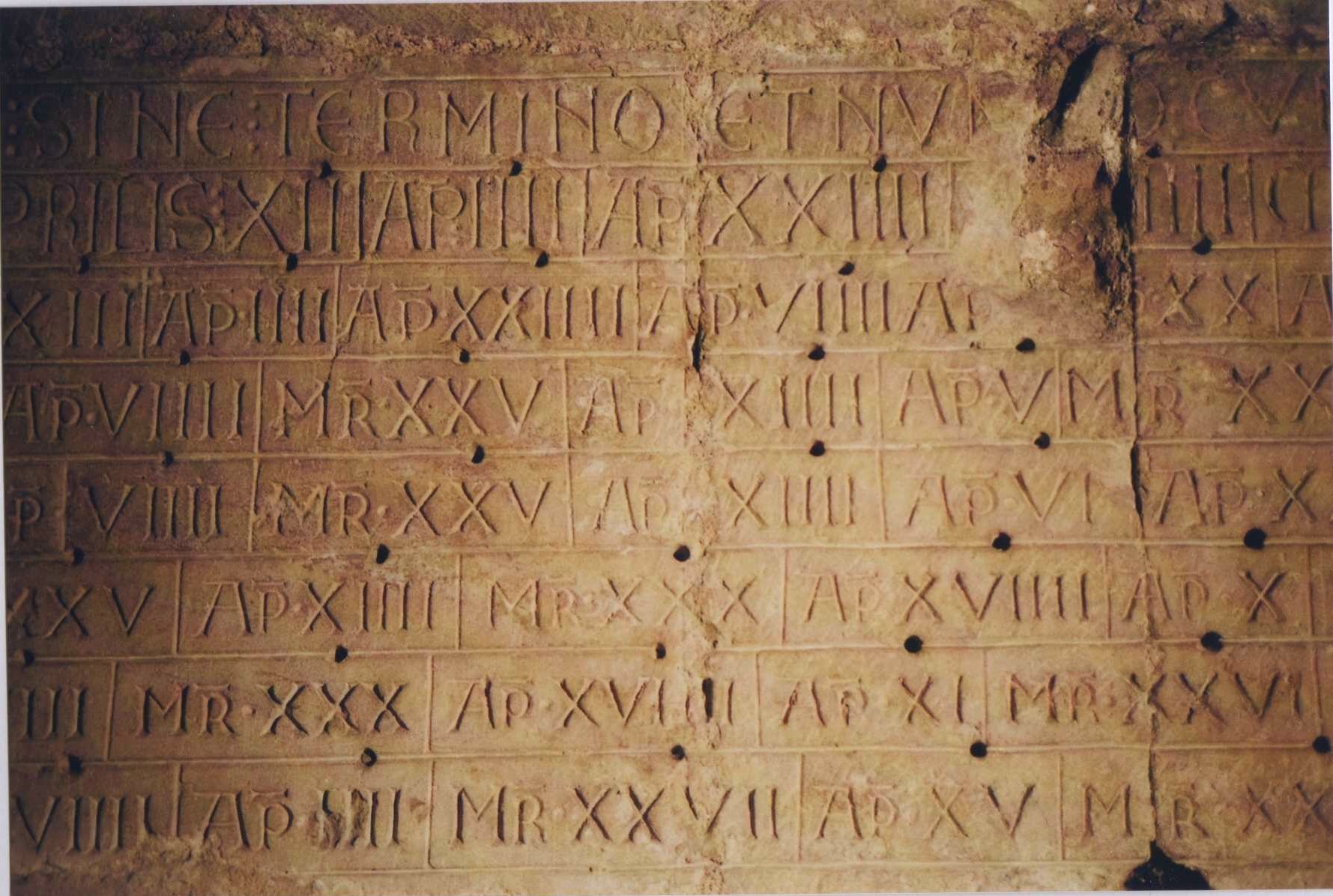

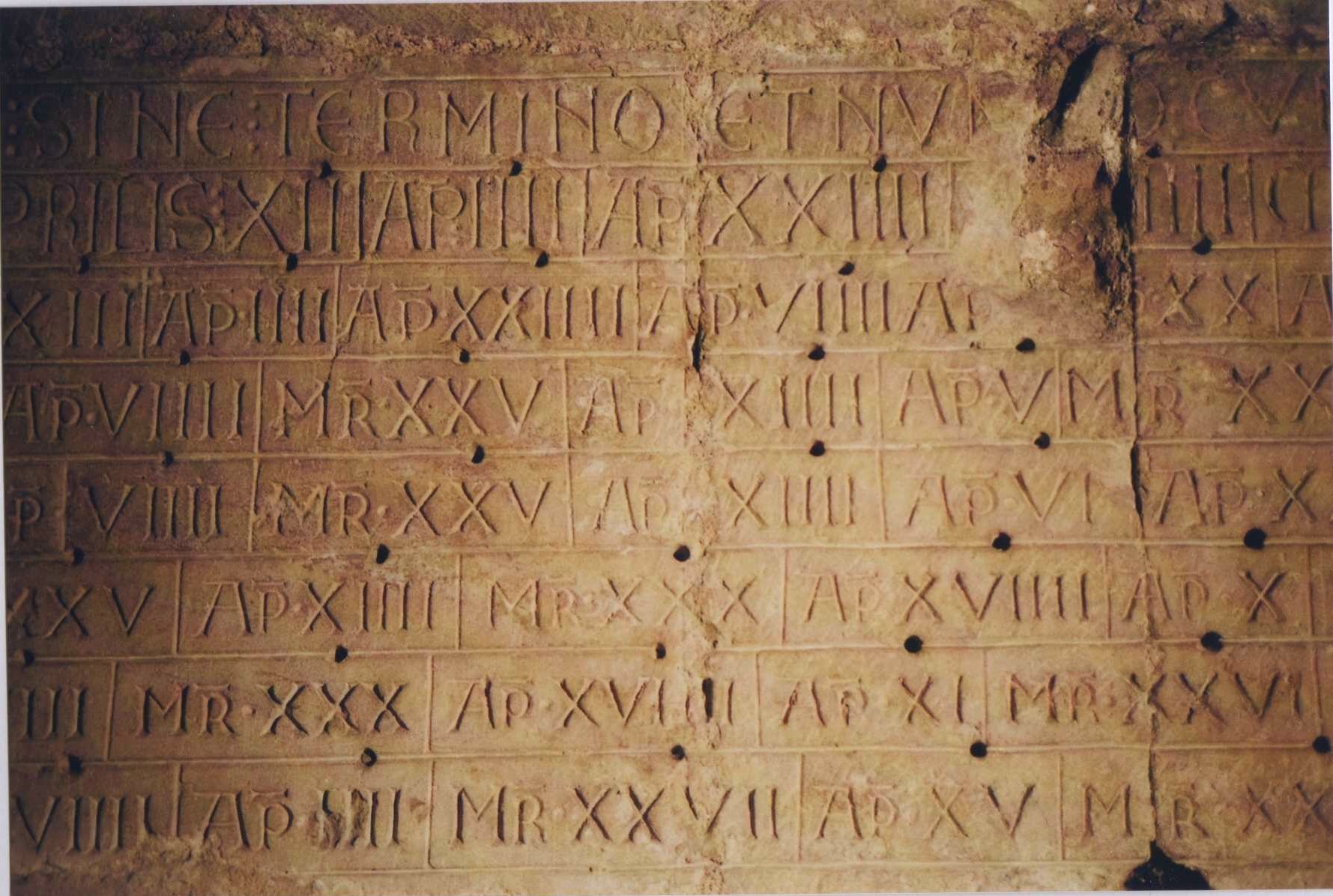

Fotography of the inscription (by Uwe Topper 2010)

Fotography of the inscription (by Uwe Topper 2010)

In both of them there are precious references to earlier literature on the subject, but so far I was not able to locate them. So I follow these two sources for the history of investigation concerning the inscription.

The inscription with Easter dates is described as a plate or slab in the church of Saint-Étienne de la Cité which had been the ancient cathedral of Périgueux until it was destroyed in 1577 . Luckily the two Eastern compartments of the cathedral were saved and are restored as parish church. With them the inscription located in the southern wall of the altar-room has survived and can be visited by everybody; it is even illuminated by a special lamp. I made a rough sketch and took some fotos.

There are 8 lines of 173 cm length and 40.5 cm hight with an additional piece of three short lines at the right hand bottom. The letters are around 3 cm high and nearly all easily to decipher i.e. well preserved. The upper line has a text in latin, all other letters and numbers refer to Easter dates. At the the last short line there is a little blank suggesting that the dates should continue but due to some unknown reason they stop here. Every date has a little drilled hole which probably once was used to allocate a small metallic or wooden pointer to indicate the Easter date pertaining to the current year. There are no indications to the phase of the moon (as in some medieval manuscripts) which makes it probable that the list of dates had only a practical purpose of use in the parish. (An opposite example would be the marble slab of Ravenna which could be used as computation instrument.)

The upper line reads:

HOC EST PASCHA SINE TERMINO ET NVM(ER)O CVM FINIERIT A CAPITE REINCIPE

which means:

“This is Easter without term or number. When it finishes start again from the beginning.”

Term may refer to the moon phase, number to the Golden Number of the year. Both are unnecessary when a simple parisher wanted to consult the list.

The first part could be understood in a different way, i.e. “Here are the Easter dates without end (termination) and number of the year.” (Corpus 1979). As to the second part all interpreters agree: Supposed that the list was complete with all 95 dates (the last four are missing), the maker assumed it to be an eternally valid list of Easter dates running through the centuries without interruption.

The Easter dates are not given in the usual latin code as habitual for church datings until around 1700 (ides, nones and calendes) but as month (abbreviated as MR for March and AP for April) with a Roman number following. This notation comes in the same manner as laics from 1500 onwards introduced it in daily life. So MR XXIIII means 24th of March.

Rough drawing of the inscription (by Uwe Topper 2010)

Rough drawing of the inscription (by Uwe Topper 2010)

These are the dates in our own way of writing:

24.3.

12.4.

4.4.

24.4.

9.4.

31.3.

20.4.

5.4.

28.3.

16.4.

8.4.

24.3.

13.4.

4.4.

24.4.

9.4.

1.4.

20.4.

5.4.

28.3.

17.4.

1.4.

21.4.

13.4.

29.3.

17.4.

9.4.

25.3.

14.4.

5.4.

28.3

10.4.

2.4.

21.4.

6.4.

29.3.

18.4.

9.4.

25.3.

14.4.

6.4.

25.4.

10.4.

2.4.

22.4.

6.4.

29.3.

18.4.

4.4. – mistake, it should read 3.4.

25.3.

14.4.

30.3.

19.4.

10.4.

26.3.

15.4.

7.4.

29.3.

11.4.

3.4.

23.4.

14.4.

30.3.

19.4.

11.4.

26.3.

15.4.

7.4.

25.3. – mistake, it should read 23.3.

11.4.

3.4.

23.4.

8.4.

30.3.

19.4.

4.4.

27.3.

15.4.

31.3.

20.4.

12.4.

3.4.

16.4.

8.4.

31.3.

19.4.

4.4.

27.3.

16.4.

31.3.

20.4.

There are only two mistakes as far as simple mathematics is concerned.

The first mentioning of this inscription seems to be by Gruterus (Heidelberg 1602/03), various authors have referred to him later on (De Rossi, Giry, Bruno Krusch). Gruterus is said to have used a copy provided by Joseph Justus Scaliger and Pierre Pithou which was incomplete since a group of eleven dates were skipped by error and five dates are given wrong (Cordoliani 1961).

Such a bad state of the “copy” is hardly possible, I think, and it could be surmised as well that the so- called copy was a first sketch or plan for the execution of the inscription.

Cordoliani did not see the inscription in person but inserted in his article a perfect fotography taken by C. M. Jacques in 1960. It is of sufficient good quality to judge the whole inscription. Yet Cordoliani insists that this inscription is made on a marble stone slab in the choir right hand of the altar and had been missing for long time. The location is given fairly correct but the assertion of a mobile slab is wrong as the letters and numbers are engraved into the square sandstones of the southern wall of the church (right hand from the altar) as I could see myself and is easily recognizable by the old foto.

The error might be due to the common designation of the list as Easter “table”, or in comparison to the aforementioned stone slab of Ravenna. It might also give an easy escape to church authorities when the origin of the inscription is discussed – they would simply declare it to be a copy as is done so often with documents and inscriptions (so far this subterfuge has not been used on this inscription).

A veiling of the date of the artefact is necessary because the asserted date (6th or 7th century) can by no means be supported if one considers the type of letters and the way of writing the dates; they must be very young, apparently of Renaissance time like the whole structure of the church. The square building stones that form the wall have not been moved after the inscription was made which can be easily ascertained from the neat joints.

So there are two changes necessary to save the list of dates as medieval: Transpose the building backwards into the 12th century, and foreward the Easter dates from the 6th/7th to the 12th century. Now they meet. Cordoliani transposed the list from 547 (“the long time accepted date”) only by a hundred years, not enough to be plausible. Although he noticed already the two mistakes of the list, his successor (Corpus) 18 years later did not mention them but inserted a new mistake. He reprinted the same fotography of 1960.

As for dating the inscription – this is a real problem because it nowhere bears a year which is basically necessary to locate Easter in this list. Cordioliani (p.57) says in contrary that it doesn’t need a year because the author was convinced that the list was eternally valid. Even then, I think, a starting year would be indispensable. The reason for the missing starting year could be that at the time of the inscription a counting of years was not yet generally accepted. Moreover, with the pointer inserted into the corresponding hole the knowledge of a year count was deemed superfluous.

Long time the inscription had been dated to AD 547 although this could have been rejected by mathematics very promptly because already after the first ten dates the list deviates considerably. Thus only line two would coincide with calculated dates in the 6th century. Logically the year 631 should be the starting point as Cordoliani found out. But he had to assume that the first four dates of Easter (for the years 627 to 630) are missing, not the last four as is suggested by the blank at the end of the inscription.

The baptismal stone in front of the mock door and the inscription on its side-pillar (foto by Uwe Topper)

The authors of the “Corpus” (1979) transpose the inscription to the 12th century (“c. 1136” in the title is a misprint, it should read 1163 as further on in the same text). This year is suggested by another inscription which today is shown in the same church although originally this one does not belong to this building. It is engraved into the side pillar of a fake door transported to the church from some unknown place and exposed here like in a museum. According to this inscription a bishop John died on May 2nd, 1169 of the Incarnation of the Lord, after ruling nine years minus seven days in this church. The wording does not inspire any reliability to the whole question but this cannot concern us here as the two inscriptions have nothing in common but the coincidence that mathematically the Easter dates could start at 1163, i.e. in the lifetime of the said bishop. It would then run through to the year 1253 without failing. The list had been supposedly engraved for future use. The authors of this conclusion can even name a previous writer who had the same idea: Abbé Lebeuf (1749).

Why experts like Krusch or Cordoliani did not see this seems very mysterious, given the palaeographic criterium that can hardly make the inscription older than early Renaissance, at the most very late medieval time. There are obvious blunders like MARCIVS with C instead of T or the two ways of writing E and M : round as well as square.

Part of the inscription of Easter dates (foto by Uwe Topper 2010)

So what can be deduced from the inscription after all?

The main assertion of the list is expressed in the first line: that it gives an everlasting sequence of Easter dates. Of course we understand – all interpreters did – that the (fragmentary) list has to name the 95 dates completely (instead of only 91) in order to fulfill its promise. But even then the “eternity” would brake up after three sequences resp. 285 years at the most. Moreover there remains the limitation that only the middle sequence would give exact Easter dates while in the first and last group of 95 dates every one in four dates would be short or late by one day, a fact that can be allowed generously as unimportant because Easter has to be on a Sunday anyhow. The alternance is due to our Julian leap year as 95 is not divisible by four.

After 285 years the list would cease to be usable, and this contradicts the first line. Could the originators be so badly informed in mathematics? Hardly possible. Or did they use a slightly different type of calender which had leap years at other than the Julian intervalls? For example, did they use the Sacrobsoco emmendation that proposed to skip one leap day in 288 years using the information about the lenght of the tropical year given in the Almagest and traced back there to Hipparch?

In such a case the list is “perpetuum”, indeed.

We can only surmise why four dates of Easter are missing in the inscription. The mason may have made an error when once giving MARCIVS in full thus missing space for one date. In the end he could not continue because space became short, but I think he could have filled in one more date at least (there is a blank) or even enlarged his space by adding another line. So another reason should be proposed: The list was not completed because the destruction of the church took place. This would give a fixed date for it: 1577. Or: the designed list was not completed yet by the computist when the mason was already at work. Or the engraving had been interrupted by church authorities after rejecting the Sacrobosco proposal for emmendation (latest possible date: during the Calender Commission’s work, around 1577 as well).

I do not consider the dating of the inscription into the 12th century as realistic. If it had any value at all, then it should be in Renaissance time, roughly in the 16th century. Starting the year in March 1st as was practice in many catholic diocesis, and starting with the year AD 1501, the list would apply to the Easter dates of its time just like the stone slab of Ravenna does. The Sacrobsoco emmendation was then under discussion as many publications show, and it had chances to be accepted because it implied a jump over ten days (in order to place the equinox on its traditional date) which in fact was put into practice shortly after by Gregor XIII in 1582. However, this correction did not accept the Sacrobsoco leap year exception (1 day in 288 years) on account of using a far more exact year length, that of Ulugh Beg (15th century) called “Alfonsine year”, thus omitting a leap day thrice in 400 years and by this making the inscription of Périgueux invalid.

Uwe Topper, Berlin, Dec. 13th, 2010

Addenda:

In Octobre 2011 my son Alexander Topper went to Périgueux and made another drawing of the table which is more precise than mine. He noted all holes of the parapegmata and has all dates correct, e.g. right hand down AP IIII and MR XXXI (in my sketch both entries miss a I).

One more point could be cleared: I had suggested that the mason could have filled in one more date at least (there is a blank) or even enlarged his space by adding another line. Alexander observed the Easter table very detailed and found out that there is in fact a space cleared by cisel for another line just below the small rectangle at the right continuing the last line. So the intention of enlarging the 84 dates to 95 is strongly suggested.

At the left wall of the same first hall of the church just opposite to the Easter dates inscription he discovered another inscription in the same style of writing and masonry filling two long framed lines reading

PRESUL: PETRVS:ERAT:IACET:hIC:INPVLVERE:PVLVIS:

SIT:CELUMREQVIES:SIT:SIBI:VITA:DEVS:OBIIT:DECiMA:DIE:APRILIS:

(I translate roughly: Before Peter he was, now he lies in dust, and dust he shall be; heaven will be his recovery as God is life to him; he died on April tenth).

There is assumedly a connection to the table. The year of death is not given, as often occurs on tombstones. Since the day of the month is stated (instead of the usual church custom of latin counting backward the days form the kalendas or ides or nones) the inscription is rather young and should pertain to the 16th century. No familiy name or title of the dead person is given, only Peter, which is rather strange.

Uwe Topper March 2012

More postscripts to this article:

In 2011 Michael Deckers wrote an intriguing commentary to this article after which we had a fruitful discussion by email. After some time I consulted Ulrich Voigt, and we three exchanged our thoughts about the matter. I am thankful to both correspondents.

I now understand that the assumption, Sacrobosco’s project of Calender Reform could solve the problem, has no backing by written sources of the time but rather remained a conjecture.

Michael Deckers concluded on Nov. 10, 2011:

“There is a couple of undisputable facts about the Périgueux table:

[a] all the dates in the table use the Julian calendar, every fourth year being a leap year;

[b] the given Easter dates are Julian Easter dates (except for the two errors) if and only if the first year of the table is J0631 or J1163;

[c] the author (or the authors) intended to show a period for the Easter dates, but no such period is shown — the table is incomplete and shows signs that additional dates should be added later;

[d] the author was not able to conceive the complete table at the start of the endeavor — hence he must have been unable to compute (or otherwise obtain) Easter dates for the remaining years in the future;

[e] before the author abandoned the project, he did not know that the period of the Easter dates he used in the table was 532 years.”

To one point I did object: point [b] „the given Easter dates are Julian Easter dates (except for

the two errors) if and only if the first year of the table is J0631 or J1163“.

My objection goes back to our (Alexander and Uwe Topper‘s) discovery some years ago, that the Ravenna calender stone (an Easter table of 95 dates similar to this one) could also be applied to the years 1501 to 1595 if its dates were interpreted as dates of the Julian calendar, with March 1st taken to be the first day of the year (which was quite common in Western Europe in the 16th century; the Pope only hesitatingly switched to January 1st late in the 17th century).

This of course does not mean that the author of the Périgueux table was aware that his dates could not be used indefinitely.

Ulrich Voigt does not think point [d] to be conclusive.

Finally, I extract some of the points from Krusch, Bruno (1884): “Die Einführung des griechischen Paschalritus im Abendland” in: Neues Archiv, Bd. IX, S. 129-141:

Krusch did not see the original table of Périgueux with his own eyes. He still talks about a marble plate, which it definitely is not. It is simply an inscription ciselled into the wall of the church. Had he visited the place he probably would have realized, that it is of very young date, presumably Renaissance time. Yet he did not even consider the 12./13th centuries as possible. He only postponed it by a century from the 5th proposed by Gruterus and De Rossi, to the 7th century, beginning the table with year 6 of a cycle of 19 in the year AD 631. This way the dates – except for the two mistakes – are all correct, and Krusch (p. 130) concludes that the Périgueux table „zeigt sich als eine der correctesten Osterlisten, die wir haben” (“one of the least faulty Easter tables known to us.“)

He goes on explaining that this table follows the same Greek scheme as that of Dionysius Exiguus. Would it start at 627 then it would end in 721 just as the Italian table of abbot Felix. This is another example for the custom to bring Easter tables of 95 years in a row. Krusch points out that to accomplish this, only some modifications have to be done as Dionysius already indicated in his Prologue.

Uwe Topper Mai 30th, 2012