Revival of an ancient Maya calendar

Our previous article “History through the filter of the 19th century”, explains how certain peoples today concoct the history of their ancestors, supported by European academia: they remain ignorant of their real tradition, which has been lost or destroyed. One example of this procedure has come to light in Central America: the announcement of a historical date for the hypothetical beginning of the Maya culture.

It seems to us that the modern day Tzotzil or Lacandons has really nothing to do with archaeologically and palaeographically determined calendar cycles. Today’s descendants of the Maya are probably unaware of this academic debate.

Part 1

How the media hype about ‘the end of the world at the winter solstice in 2012 came about, was initially unclear. Statements by politicians, about this projected end of the world, wanting to carefully downplay this whole affair, as if there really was a widespread general hysteria. It is clear that this prophecy was a media hype, that television viewers should find amusing; it has nothing to do with Maya of today, nor with any scholarly debate surrounding the Maya of the Classical period.

Is there a connection ?

As far as can be seen, the North American art historian and painter José Argüelles (Minnesota 1939-2011), claiming dignitary status from modern-day Maya, first promoted this date. Argüelles taught as a professor at Princeton and other universities in the USA. He invented several calendars, one called “Dreamspell”, based on Mayan numerals with the Chinese oracle book I Ching. He did not claim this was a genuine Mayan calendar, but one usable universally. Allegedly many people all over the world, use this calendar with oracular connections in their daily lives.

A statement of his caught our eye: “On the winter solstice in 2012, the sun will be in conjunction with the equator of the Milky Way, triggering a change that will affect the world.” The conjunction mentioned is not any astronomical fixed point- yet ‘the solstice’ is? This ‘solstice’ is mentioned in this context, with other dates announced in the last few years. Argüelles connects the Revelation of St. John with the Mayan calendar because it uses the same (or similar) numbers. With the “Harmonic Convergence” on August 16/17, 1987, he first drew the attention of the public to the “end of times” of the Mayan calendar and an imminent “qualitative leap in human history”. He took this date as the end of an epoch of 22 cycles (each of 52 years), going back 1144 years, with its beginning around the 8th century AD. That might be confirmed by archaeological finds. From a sarcophagus inscription from the 7th century AD, he then deduced that on the winter solstice 2012, December 21st, at 11:12 GMT, a new world age would begin.

Mayan elders have disdained using the Mayan calendar in this sense.

It is completely impossible to connect any calendar dates appearing scattered among the Mesoamerican pre-Columbian inscriptions, with our current Gregorian calendar. Even if one had attempted this when the Spanish bishop first explorer of the Aztecs, Bernardino de Sahagun (1499-1590), tied a date of the pre-Christian Central American calendar to a specific Christmas or Easter day, this date could not be related to any inscription dates. This was all decreed by the Catholic church, to disencourage any and all pagan customs, common practice at the time.

Over the past hundred and fifty years, Americanists academically trained in both the Old and New Worlds, have made constant efforts to decode and date these prehistoric inscriptions of Central America, associating calendar dates found there with the Gregorian. The results are various, as is all Mayan research, sometimes varying by four hundred years. What they all have in common: Most of the data can be no more than 1200 years old, probably less than one millennium- according to the shorter chronology it might be only about 800 years old.

That wouldn’t be so bad – but now comes the worrying yet humorous aspect of this problem – it is evident from simple mathematical calculations, that the Mayan calendar reconstructed by these Americanists goes back at least five thousand years. This does not even vaguely fit with the archaeological evidence, which does have historical support: Alonso de Zorita wrote in 1540 that the texts of the numerous native books he saw, translated to him, reported historical events going back only eight centuries. This almost corresponds to the period assigned to the oldest inscriptions on the buildings. The extent to which this attribution is confirmed by Zorita’s specification must be further explored.

Recently discovered in Guatemala is an inscription presented by William A. Saturno as the oldest Mayan astronomical calendar (published in Science 4/5/2012). He dates it to the 9th century AD. With the latest knowledge about the Olmec, a “predecessor people” of the Maya, one goes back at most two thousand years for the earliest beginning of writing in Central America (see “Olmec” in http://ilya.it/antropologo/Felsbilder).

Part 2

Which brings us to the actual question: What is the use of a calendar whose starting date ranges freely over thousands of years and whose internal mechanism do not allow any real solar or lunar year to run?

This should be clear to any researcher: These three calendars used by the Maya are not astronomically justified. They are only partially reminiscent of ancient oriental cycles, especially the one called “Haab”, using a cycle of 18 months of 20 days plus five uncounted “bad” days corresponding to the Egyptian solar year of 365 days. Skipping the quarter day, the beginning of spring (to give just one example) is already five days wrong after twenty years, i.e. by exactly this number of “bad” days inserted. One could skip these five days if they don’t matter. The Spanish bishop, expert on Maya culture, Diego de Landa (1524-1579), reported the Maya switched their quarter day as a whole day every four years- for which there is only his testimony. However, it does appear this widely admired interlocking of the Haab and Tzolkin calendar cannot work as assumed.

The second calendar (called “Tzolkin” in academia) is even more abstract: this “year” has 260 days, made up of 13 months of 20 days. The sum is not even a close match in the sky, it may compare to a woman’s pregnancy counting from the beginning of her first missed period. It is allleged that ‘a certain variety of corn’, no matter when planted, takes 260 days to mature.

Philologist Barbara Tedlock from Buffalo University in New York researched the traditional profession of calendar keeper (with her husband Dennis) for many years, in a surviving group of the Maya culture in Guatemala. In an interview documentary film director David Lebrun did with this couple in February 2005, she explains in detail how the calendar is used today. The calendar may be in use by 85 villages. A calendar keeper must memorise the specific meaning of each of the 13 x 20 = 260 days (bad days, good days, a day to reflect, to get angry, to settle money matters…), the associated names for naming a child, etc. ; he or she must also interpret dreams. However, the word Tzolkin, used today for this calendar; it is a modern coinage; in Guatemala it would called Rahil Bahir, meaning ‘days cycle’.

Are there continuous traditions connecting us to historical Maya empires? Yes, says Ms. Tedlock, there is a play, Rabinal Achi, with a historical provenance, having been banned a dozens times between 1590 and 1770. As a holy service it is still performed: In this piece, the 260-day calendar is mentioned several times. We do not know whether the current sequence of days, of this only surviving Mayan calendar, continues from the original without a break or was a revival. It only compares two thirds of a year and the expired cycles were not counted, any equation with our calendar is impossible. Today’s equation is fixed.

The third calendar is the only one that has been used for historical purposes; it is called the “Long Count,” which was used as a historical measure for longer periods of time on their murals. The basic units are again 20 and 13, but here reinforced by two more rows of 20:

A tun is set at 360 days, (similar to the truncated year of the Babylonians). 20 tuns make a katun of 7200 days (360 times 20), which is roughly 20 solar years. This is multiplied by twenty again, giving 144,000 days, a significant sum for Christians (the number of the redeemed in the Revelation of St. John). It is called Baktun and close to 400 Gregorian years. If you take 13 baktun (the magic number of the Maya), you get 5200 years, which would be their zero year: Everything is pure number theory. Harmonising it to any old-world annual count, to any astronomical event, has been unsuccessful, though many attempts have been made. The Baktun count (baktun yet another modern word), according to Americanists, was long out of use by the time the Spanish reached Central America.

Baktun 13 plays an important role as the end of the great cycle, but this value has only been found on a single monument, the so-called Tortuguero No. 6, which has become partially illegible and dates from around the 7th century AD. Hardly anything can be clarified with this single clue. Nevertheless, a very early start date is claimed for the “Long Count” in particular, because it results from the calculation if one assumes an end date: The entire process is about 5128 real solar years. That would be thousands of years before any archaeological evidence of local cultures.

The archaeologist Maud W. Makemson put the concise end date 13.0.0.0.0. equal to our year 1752. The copious literature on the subject shows that the mathematical evaluation is inconsistent, not just by days but by years. The principle of today’s equation goes back to John Eric Thompson (London 1898-1975). He was a doctor and expert on Mayan culture, a bitter opponent of the decipherer of Mayan writing, the Russian scientist Yuri Knorozov (1922-1999), whose views prevailed after Thompson’s death and allowed the reading of the Mayan glyphs. Thompson had been conducting research in the Yucatán since 1926 and monopolised Mayan science to such an extent that his successor, Michael D. Coe, after Thompson’s death, has claimed that only now (40 years later) can the deciphering of Mayan writing begin.

While Thompson placed the Madrid Codex at 1250-1450, Coe placed this important piece of evidence as post-Spanish conquest, which may also apply to the other two codices in Maya glyphs. Modern study of Mesoamerican cultures began quite abruptly with Stephens and Catherwood around 1840. Their first publication of 1841 was followed by another in 1843 with an appendix by J. Pio Pérez, who, using pieces of manuscript put together, discussed the ancient Mayan calendar, as described at López de Cogolludo (1688).

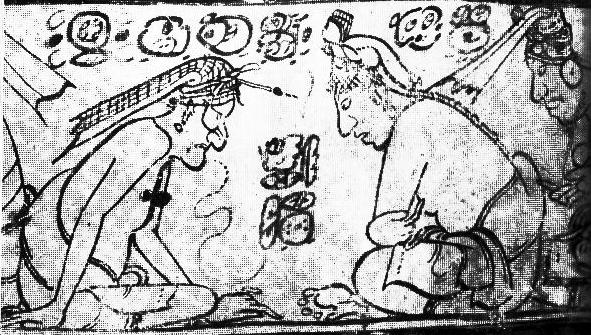

Most connoisseurs consider three Maya manuscripts to be pre-Hispanic: The oldest is the Dresden Codex, appearing in Vienna as early as 1739. Of the 350 different characters in the codex, about 250 are legible today; most of them correspond to the alphabet that Bishop Landa recorded in 1566 (after destroying all the original texts). Inscriptions on steles at Chichen Itza sometimes use similar glyphs. Unfortunately, the entire text is incomplete, and the days of the Tzolkin calendar are often left out. Six writers are identified.

The second, the Paris codex, existing since 1832 and also signed 3 years later, of which a single copy is in Chicago, while the original drawing was lost, but the codex itself disappeared again until 1859, when the East Asia specialist Léon de Rosny (1837- 1914) pulled it out of a rubbish bin in the chimney corner of the Bibliothèque Impériale in Paris. It was first called Peresianus after José Pérez, whose name was found on the wrapping paper. José Pérez published two short descriptions of the codex in the same year. Today it is called Codex Parisianus and is kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. It is considered genuine.

THE Madrid Codex had an even stranger fate. It consists of two pieces the larger of 70 pages (called Troano) was discovered in Madrid in 1866 by the French scholar Charles Brasseur de Bourbourg (1814-74); a second piece of 22 pages (called Cortesianus) went on sale in Paris and London in 1867, but found a buyer only in 1872 and was (1875?) sold on to the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid. Rosny recognised in 1880 these two parts belonged together and in 1888 they were united. These are glyphs of the kind recorded by Landa. The writing is from 8 scribes, the text is said to have been “hastily” put together according to various sources.

A fourth codex, a fragment of eleven pages, is called the Grolier. It appeared in 1971, is disputed and very likely- see J.E. Thompson (1975), Claude Baudez (2002), Susan Milbrath (2002) and others- is a modern forgery on old paper, probably written in 1960 after L. E. Sotelo. It seems possible to us that after the public burning of all pagan writings by Diego de Landa in 1562, none survived so any sources available today were created on paper, under the supervision – even with the participation of Catholic priests.

The later Maya texts are therefore important, such as the Popul Vuh, written by Francisco Ximénez in the 16th century, published in German by Scherzer in 1857, in 1861 in the original text by Brasseur, who also published a dictionary in the same year, as well as the one afore-mentioned play, Rabinal Achi (1862) and part of the report (Relación) of Landa (1864).

These often mentioned astronomical skills of the ancient Maya are disputed by many experts; Equinoxes and solstices were not celebrated, not even noted. Only the observation of Venus received more attention in writing; in the Dresden Codex nine pages are filled with information about the heliacal rise of Venus. The rising of this planet was allegedly accompanied by bloody human sacrifice and ritual anthropophagy. The extent to which this constitutes Christian slander has- so far- been disputed but Venus was important to the Maya because ‘they started their wars at its rising’. It is unclear whether this sequence in the codex is a matter of predictions or historical observations of Venus. The various statements from experts on the data, range from ” a few days are correct” (J. E. Teeple) to “very accurate, based on observations over centuries” (Rolf Müller).

These Venusian dates should match those from Babylonia from the 1st half of the 2nd millennium. B.C., being (almost) exactly the same (almost 3000 years separate the two data series).

Let’s take a look at the process of dating the calendar dates on the stone inscriptions. After the first chronological attempts in the 19th century, Joseph T. Goodman (1838-1917) published his idea of a connection between Mayan dates and the Christian number line in 1905. J. Martínez Hernández improved this approach in 1926, and the next year Thompson’s equation finally appeared, since called the GMT equation, referencing all three authors. It is based in part on Landa’s note for the “Short Count”- although it is unclear which year Landa referred to; Thompson accepted 1553.

In addition to the GMT equation, there are a number of other equations to our annual count, ranging up to twice the lowest number. Inscriptions were also cited that ran over more than 13 baktun, up to 19 baktun (on a stele in Cobá), whereby conversion resulted in very high numbers, presumably having a religious character; which is also common from lower Maya calendar numbers as accepted.

Wikipedia’s view is as follows: The date of death of the ruler Pakal of Palenque is set by Thompson to 28 August 683 AD. Using this basis, other calendar dates then equate with our historical annual count. Proleptically recalculated, the beginning of the “Long Count” corresponds to Gregorian August 11, 3114 BC, Thompson describing as the Maya’s World Creation Day. Just as any recalculation of a Julian date by Scaliger or that of a proleptic Gregorian date are purely mathematical actions, so is this equation with Mayan dates. A historical reference is not achieved.

Part 3

It is exceedingly difficult to trace exactly who first applied the dating contained in Thompson’s equation of the hypothetical beginning of the “Long Count” to an end of the cycle of the 13 baktun. Coe in 1966 put the end of the cycle on Christmas Eve (December 24) 2011, then (2nd ed., 1980) on January 13, 2013 (the 13 is very important), then (3rd ed. 1984) on Dec 23 2012. Sylvanus G. Morley (Carnegie Institute, 1883-1948) wrote The Ancient Maya in 1946, posthumously reprinted in 1983 and revised by Maya scholar Robert J. Sharer (Pennsylvania University), including a plaque, where the end date of the “Long Count” correlates with Dec. 21, 2012.

It is also claimed that the above-mentioned Argüelles chose a number symbolically particularly concise date as the initial number: August 13, 3113 BC. The number 13, which is so important for the Baktun cycles, and (after the month) “the same” number reversed as 31, followed by another 13. In this context, the Maya culture is equated with the ancient world high cultures. The reasoning going something like this: “If you look back in history, you will find in most Western history books, around 3100 B.C. BC civilisation began. This is 13 years after the Maya Long Count. Now, to be precise, according to our calendar, that would be August 13, 3113 BC. The city of Uruk was also founded around 3100 BC. founded, and the Kali Yuga of the Indians began in 3102 B.C. Chr.” The archaeo-astronomer and connoisseur of the Maya, Anthony Aveni, rejects this date. In 1975, under the influence of Mexico’s intoxicating mushroom (psilocybin), Terence McKenna (“The Invisible Landscape”) propagated a kind of end-of-time, based on I Ching, for November 16, 2012. In the 2nd edition, 1993, Morley proposed the date (“The Ancient Maya” 4th , 1983) taken over on December 21, 2012, because he came up with it through a meeting with José Argüelles in 1985; Incidentally, from this meeting onwards, Argüelles includes this year 2012 in his work.

So, it now appears that it was Terence McKenna (1946-2000) who promulgated this date of the winter solstice (December 21) 2012 being ‘the end of the world’. There was also the very popular North American TV series “The X-Files” where in the final chapter (“The Truth”) FBI agents pursue someone who believes in alien invasions on December 22, 2012 due to the Mayan cycle. She introduces a plot by the American government to cover up an alien invasion. This series is pure science fiction, not meant to be documentary but she nonetheless helped bring this supposed Mayan prediction to an enormous audience: 13 million viewers saw the programme. So, it might be McKenna supporters who believed in this date, or readers of the American writer and journalist Daniel Pinchbeck (*1966), who also claimed to be inspired by Quetzalcoatl and processed McKenna and Argüelles.

Assigning certain concepts of the so-called Tzolkin calendar is reminiscent of old-world magical writings: Probably why it was easy for Argüelles and McKenna to link the Maya system to the book I Ching.

Part 4

Well, the modern Maya did indeed celebrate this day, December 21, 2012, with much ceremony. While they did not expect the end of the world, but simply celebrated the festivities of a calendar cycle end, this cycle seems to stem from academic calculations, not from within their tradition. Three Mayan deputies, among them recipients of a ‘human rights award’, travelled to Cuba a few weeks earlier, performing a small ceremony there to announce the calendar change. Among them was the well-known human rights activist Rosalinda Tuyuc (*1956, Member of Parliament and Vice-President of the Parliament of Guatemala in the 1990s; Ordre Legion d’honneur 1994), and she too took December 21, 2012 for granted, although like all other Maya interviewed spoke out against any definitive “end of the world”. There is a Guatemalan government website that explains the Maya calendar in detail, albeit using the past tense (“the Maya had…”); illustrations are drawn after J. Eric Thompson according to the source. The date was indeed big and officially celebrated. The President of Guatemala himself, Otto Pérez, in the presence of his Costa Rican counterpart, opened the ceremony in Tikal, in the Petén district, at one of the 13 Mayan shrines where celebrations took place. There were traditional dances in feather robes that really looked like the prehistoric images, and there were “revivals” (recreaciones) of the ancient Mayan ball game. Well-known rock musicians came, playing traditional Mayan music, some on traditional musical instruments; flutes, bull horns, conches, drums, turtle shells, but above all chirimías, wooden “shawms” introduced by the Spaniards in the 16th century and absolutely part of the tradition today.

There was even the spectacle of the “Moros y Cristianos” (Moors and Christians, from the time of the Christianisation of Spain), a traditional rite in the Petén area, now popular and promoted, as well as Catholic sacred images. Emphasis was placed on conducting a genuine folk celebration, syncretic as folk celebrations are, not some aloof consecration for a few revivalists. Unfortunately, as announced afterwards, one Tikal temple was damaged by the many tourists climbing up it. According to official estimates, this year saw 200,000 more tourists than usual, an 8% increase over other years, attracted by these celebrations.

In Honduras, President Porfirio Lobo opened an official celebration during which he underscored December 21 as the end of a Mayan cycle hopefully the beginning of a better era.

In conclusion, Mayan human rights activists and intellectuals are successfully saving their still existing culture, basing it on real folk tradition. People are not afraid to adopt elements only existing in recent centuries; today’s culture of the real Maya of the 20th Century can be saved. For a better connection to the culture of the historical Maya, which was actually continued, particular elements are revived, among them their traditional calendar, correlated with the Gregorian -with the help of academic North American research- or actually conjectured to thus becomes applicable. This is exactly the typical model which we call “history filter”.

The prophecy of the end of the world, which arose from the hallucinations of some intoxicated visionaries in California, is a popular topic of entertainment in the press an effective trigger for raising awareness of this revival. It is also always emphasised by historians that the Maya believed that certain cycles of their calendar were associated with catastrophes and disasters. In this sense the Mayan conception resembles the Christian.

Finally, once again our chronology-critical statement: The yearly counting of the Maya, which is thoroughly theologically structured, cannot be connected with the yearly counting, which is based on Christianity, because any connecting link is missing. This much is obvious to anyone. Thompson made a connection that is scientifically untenable and inconsistent with the archaeological record.

This end of the world hysteria was helpful in spreading the date; partly it was a triggering hook for the popularity, also in terms of content, because the end of the ages was repeatedly emphasised in the Popul Vuh, and also because it fits to the codices (especially the Dresdner), which were probably written under the supervision of Catholic priests: Were it not for John’s Apocalypse, we might not have heard of these celebrations. The basic apocalyptic pattern has been a guarantee for revival. It is also important that the end of the cycle was placed on the solstice! The whole idea that a Maya chronology should run from a certain date in the past to the future seems based on the arbitrary reading of European and American scholars, who have in mind the one-way timeline of the West instead of the Maya’s cyclical concepts of time.

References:

Brewer of Bourbourg, Ch. SAY. (1857): History … of Mexico … (Paris) – (1861): Popul Vuh

Coe, William R. (1980): Tikal. A Handbook of the Ancient Maya Ruins (Univ. Mus. Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA)

Danien , Elin C. and Sharer , Robert J. ( 1992 ): New Theories on Ancient Maya (Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, USA) .

Landa, Diego de (1566): Relation of the Things of Yucatan (dtsch: Reclam 1990)

Lopez de Cogolludo (1688): History of Yucatan (Nachdruck Merida 1842-45)

Müller Rolf (1966): The Planets and Their Worlds (Berlin)

Pérez, José (1859): „On an old unpublished American manuscript“, in: Oriental and American Review, Paris, vol. I, pp 35-38

Pérez, Juan Pio (1846): Ancient Yucatecan Chronology (Merida)

Rosny, Leon de (1878): The Codex Troano and the Hieratic Writing of Central America

Sahagun, Bernardino de (b. 1569): General History of the Things of New Spain (Abschrift found 1783, veröfftl. ab 1829)

Teeple, J. E. (1926): Maya Inscriptions: The Venus Calendar and Another Correlation, in: American Anthropologist, vol. XXVIII, pp. 402-8

Thompson, J. Eric (1935): Maya Chronology: The Correlation Question, in: Contributions to American Archaeology nr. 14, Oct. 1935)

Ilya and Uwe Topper, December 2012

Addition: An unnamed joker sent us the following joke to loosen things up, which we insert here at the end.

The solution to the riddle: “The Maya distinguished between two different types of zero when specifying dates and periods of time.”

(Images freely adapted from André Cauly and Joan Hoppar)

English translation by Nick Weech.